Table of Contents

Constantinople Saved by Sports Fans - The Rivalry of Blues and Greens

Little does one know about history if he thinks that only kings and generals were those able to save the day. Heroes existed everywhere, not only on battlefields and in royal palaces. Moreover, history showed us many times that armies of thousands, fleets and weapons were not enough to save from disaster. It was not the power, but the passion that usually saved the day. There were times when it was the passion of sports fans. In late Ancient history, Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, had the most passionate fans there were - the Blues and the Greens. If it wasn’t for them, the city would have surely witnessed the rage of one of the greatest raiders of all time - Attila the Hun.

Hunnic Threat

The Huns became a threat to the Eastern Roman Empire in the late 4th century, when they arrived in the Great Hungarian Plain. Establishing a base just north of the Roman military border - the Limes, Huns became nightmare neighbours for Eastern Romans. The weakened empire was not able to hold these hordes of “wild” warriors.

Emperor Theodosius I (379 to 395) tried to make use of them in his war against the Goths, but the Huns turned out to be allies from hell. In pauses between fighting Goths, Huns pillaged wealthy cities from the Danube to the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea. From their employers, Eastern Roman Emperors became hostages of the Huns. Seven hundred pounds of gold was the annual tribute they had to pay Huns not to pillage Roman lands.

However, as soon as the Huns would engage their forces in some other part of Europe, Eastern Roman emperors would stop paying tributes. It was a risky gamble that Romans always paid dearly. Atilla, the leader of Huns despised Romans, especially their treason and haughtiness. Each time he made them pay for it by pillaging their wealthy lands.

In 443, young Atilla became the sole ruler of his people after his brother Bleda died. Emperor Theodosius II (408 to 450) tried his luck by not paying the arranged tribute. Atilla was the younger brother, the weaker one, he assumed. He believed that the Empire was capable of withholding a young leader.

Little did Emperor Theodosius II learn from the past. With ease, the Huns broke the border defence and rushed southwards. Atilla was asking for the gold his people were promised. There was no way he would enter any kind of negotiations Emperor Theodosius II proposed. It was either gold or pillaging.

Emperor Theodosius II was far from happy when he heard of Hunnic troops riding across his lands. Still, he was secure within the walls of his capital - the city of Constantinople. For Huns, who lacked the siege equipment and experience in using ones, the walls of Constantinople were an insurmountable obstacle.

Attila in a museum in Hungary (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Walls of Constantinople

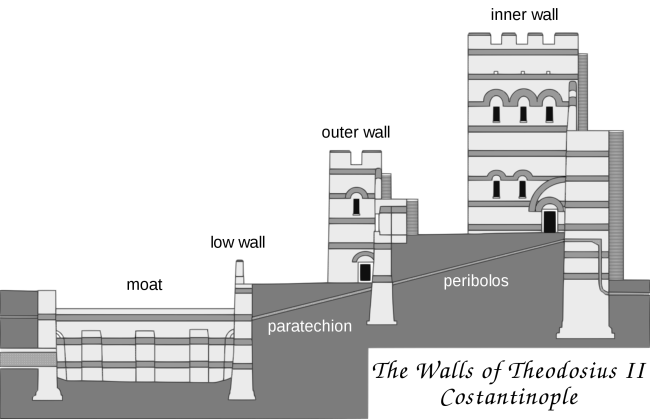

One of the great achievements of the reign of Emperor Theodosius II was the improvement of the city walls. The first wall was built by the founder of the city, Emperor Constantinus (324 to 337). By the middle of the 5th century, walls became insufficient to protect the city, which expanded beyond them. Above all, the rise of “barbarian” tribes urged the Prefect Anthemius, the patron of the underaged Theodosius, to construct the new walls as quickly as possible.

The new walls included larger areas of the city and were 5.5 km long. The wall was 12 meters high with 96 18-meter-tall towers. By 440, a second line of 8-meter-tall wall was added and the number of towers was increased to 192. The new walls offered far better protection than the city previously had. Theodosian Walls secured the city against barbarian threats for many years to come. It was these walls that protected the Empire until its last days in 1453.

On January 27, 447 a mighty earthquake struck Constantinople, causing serious damage to city buildings and newly built walls. Large sections of it were completely destroyed, along with 57 towers. In just a few moments, the city defence collapsed and the opportunity arose for the Huns to attack the city. This was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for them. With their strength, there was no doubt that they would manage to enter the city through gaps in the walls. Once inside they would have enormous plunder at their disposal.

Citizens of Constantinople were terrified with the prospect of Huns destroying their city. In processions across the city, along with the emperor and the patriarch, they prayed to God for salvation. Praetorian Prefect of the East, Flavius Constantinus took a somewhat different approach. He organized a whole army of artisans and laborers to work on repairing the walls. It was a race against time as Atilla had already received the news and started gathering an army for the raid on Constantinople. In order to speed up the work, Flavius Constantinus called for assistance from members of the chariot-race fan clubs.

The structure of the Theodosian Walls CC BY-SA 4.0

Bread and Circuses!

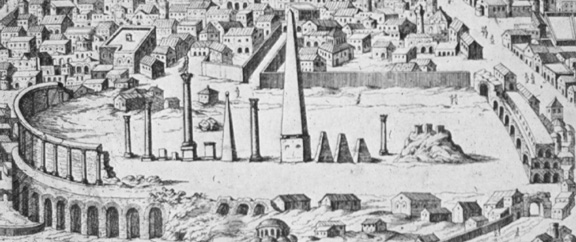

Chariot races, along with Gladiators, were extremely popular in the Roman Empire ever since the age of the Republic. Bread and Circuses! It was all the masses asked for. In Constantinople, races took place at the famous Hippodrome. It was 450 m (1,476 ft) long and 130 m (427 ft) wide glorious structure built by Emperor Constantinus that could take more than 100,000 spectators. In the middle of the Hippodrome was a race track that went around the long central barrier called the spina.

Hippodrome was not only the sports venue, but also a place where emperors could feel the pulse of the people. Chariot races were true festivals and emperors almost always attended them. Whatmore, it was the Emperor or the Prefect who funded the whole event. As they watched the race from their imperial box, the crowd would either greet or boo them. Chariot races were the only places where plain people could come in contact with their rulers.

Races comprising four, sometimes up to twelve four-horse chariots, were very exciting but extremely brutal at the same time. The tracks were extremely narrow, not more than 50 m, and made maneuvering very difficult. Especially dangerous were turns at the end of the course. Apart from the difficulties of the track, races had practically no rules and often ended up with fatal outcomes. It was a common sight for charioteers to crash each other into the walls of the track or to end up being dragged to death by their horses. The prizes for winning a race, however, were enormous. Many charioteers, who started their careers as slaves became very rich people. One of the most famous charioteers, Diocles, earned 36 million sesterces in his career. It was enough money to buy food for the entire city of Rome for one year.

Apart from being wealthy, top charioteers enjoyed a high reputation among masses. Most famous of them even had monuments erected on the central spina by their fans.

Hippodrome ruins - (Public domain)

Blues and Greens

The Charioteers were divided into teams, each with a huge and dedicated fan base. At the beginning there were four major teams: Whites, Blues, Reds and Greens. By the mid 5th century, only two teams survived: the Blues and Greens, which incorporated the Whites and Reds respectively.

During the races, fans would arrive at the Hippodrome in groups, dressed in tunics in the color of their teams. Many of them were recognizable by the same haircut. Each group had its own place on the stand. During the race, they would loudly cheer their charioteers and curse on the opponent’s. Their dedication went so far, that they even used to throw curse tablets with nails against opponent charioteers, in order to disable them.

The rivalry between the Blues and Greens was huge. It was suggested by some historians that the division went beyond the Hippodrome stands. The Blues came almost exclusively from richer parts of society, while the lower classes were Greens supporters. Blues also confessed to Orthodox Christianity, and the Greens were connected to the Monophysisist faction of the religion.

In any case, the rivalry definitively spread out from Hippodrome to the streets of Constantinople. Whether it was for sporting reasons or not, the clashes between the two groups went so far as to turn into real bloodshed. In 501, in one of the most notorious clashes, the Greens prepared an ambush for the Blues at the city’s amphitheater. The fight ended with 3,000 dead Blues fans.

Six years later, there was a great clash between two groups that turned into a full-scale riot after Porphyrius, the Greens’ ace, won the race. The victory wouldn’t have been of great importance if, a little earlier, Porphyrius hadn’t defected from the Blues camp.

The culmination of the chariot-race-inflicted riots came during the famous Nika Riot in 532. It was a rare occasion when the Greens and Blues were united in petitioning for the Emperor and City Prefect to set free their imprisoned leaders. After their demands were denied, the Blues and Greens set the city on fire. For four days, Blues and Greens were causing chaos in the city, even calling for the dethroning of Emperor Justinian. On the fifth day, during the race, the emperor’s troops surrounded the Hippodrome and attacked the Blues and Greens inside. Out of 30,000 spectators, no one survived. After the tragic event, the chariot races were abolished for some time as well as fun clubs.

Charioteer (Public Domain)

Repairing the Walls

How come then that the rivalry between two groups was used for the benefit of society? We would have to go back to Prefect Flavius Constantinus, who was in charge of repairing the city walls. Aware that the city’s capacities for such a complex undertaking were limited, he turned his attention to the Blues and Greens. He mobilised between 8,000 and 16,000 supporters from both groups to work on repairing the walls. It was clear that these guys had excess energy that could be spent for greater good.

Even though mobilisation of fan groups was a good idea, Prefect Flavius Constantinus failed to observe one important thing. Not even the danger of the Hunnic raid could have forced the Blues and Greens to work together. Even if Prefect managed to persuade them to work together, the two groups would have surely ended up in a fight in a matter of days.

The toxic rivalry inspired Prefect Flavius Constantinus to turn his good idea into a brilliant one. He organized a competition. The Blues were engaged in repairing the section of the wall from the Gate of Blachernae to the Gate of Myriandrion and the Greens from that point to the Sea of Marmara.

Once it became a matter of prestige between the two fan clubs, the supporters rolled up their sleeves and got to work. They worked for sixty days without break, day and night. The result was impressive. By the end of March, the walls were fully restored.

It was a bitter disappointment for Attila when he received the news that the walls were repaired. The glorious city of Constantinople was saved from his wrath.

Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, Istanbul - by Carole Raddato

The extraordinary success was immortalized by a marble plate that can still be seen at the Mevlevihane Gate (Mevlevihane Galata) in Istanbul. The inscription mentions:

“Constantinus, who by Theodosius’ command, triumphantly built these strong walls in less than two months. Pallas could hardly have built such a secure citadel in such a short time.”

Hardly would Flavius Constantinus earn his fame if there weren’t for the passion of no ordinary heroes - the Blues and Greens.

Further Reading

-

Cameron, Alan Douglas Edward. Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium. Clarendon Press, 1999.

-

Procopius, and Henry Bronson. Dewing. Procopius. Harvard Univ. Press, 1914.

-

Kelly, Christopher. The End of Empire: Attila the Hun & the Fall of Rome. W.W. Norton and Company, 2018.