Table of Contents

Sonderbund War - Switzerland Forged in the Civil War

When speaking of Switzerland, the first things that come to mind are banks, chocolate and neutrality. For over one and a half centuries, Switzerland has been an island of peace and prosperity, while the rest of the continent went through horrors of more than a few wars. The Switzerland everyone knows today was, however, forged in a war. More precisely, it was a civil war. It lasted for only three weeks in November of 1847 and is better known as the Sonderbund war.

Old Switzerland

The fall of Napoleon in 1815 led to the restoration of the old order in Europe. The people were denied sovereignty over their nations and, once again, the continent was embraced by aristocracy.

Such was the case with Switzerland, a country that re-established the independence lost during the Napoleonic era. Its administrative provinces, Cantons, went through the process of restoration as well, and were brought back to the rule of patricians.

The restored Switzerland became a loose confederation of 19 cantons gathered around the central council - the Diet, practically a powerless governing body. In order to carry any decision into effect, the Diet previously had to get consent from all 19 cantons. An awkward constitution, one might think. But it wasn’t to those who created it, first the foreign minister of the Austrian Empire Klemens von Metternich. It was in Austria’s best interest to have a weak and aristocratic neighbor, since in any other case Switzerland would pose a serious threat.

The Swiss patricians also preferred the country that way. The conservative constitution of the country acknowledged their aristocratic privileges, and the lack of strong central government allowed them to practice almost unlimited power over their cantons.

The large class of traders, manufacturers and intellectuals, however, were far from satisfied with such a situation. The constitution imposed offered no progress, neither in trade, industry or any other field of society. The spirit of the French Revolution was still present in their minds. With each day, this class of uncontended was growing, and so was their desire to change things.

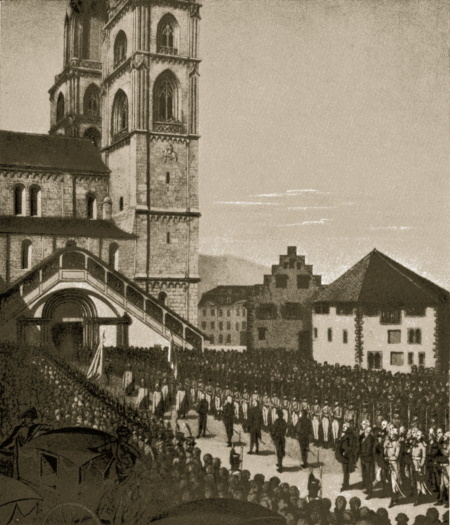

The Diet moves into the Grossmünster. Public Domain

New Switzerland

The 1830 Revolution in France was a signal that the time had come for changes to come true. In no-time, the winds of change blew across the Confederation. Conservative constitutions were overthrown in 12 cantons, establishing the rule of the people. The old aristocratic system was replaced with political equality for all.

The Diet, however, remained beyond the reach of the reforms. The attempt to change it in 1832 was met with stiff resistance from cantons under strong catholic influence. Exactly at that moment, the seed was planted for the future discord in the country. The difference between those who desired change and tighter bonds within the confederation and those who despised all change was growing with each day.

By the mid-1830s, the political scene of the Swiss Confederacy was profiled by three competing ideological groups:

The Liberals

The Liberals were advocates of the people as the sole sovereigns of the state. They promoted a common Swiss identity, stronger bonds between cantons and unified economy. Liberals spread their ideas by founding numerous societies across the entire country.

The Radicals

The Radicals shared liberal ideas, but stood against the arbitrariness of elected officials. What distinguished them was the strong anticlerical sentiment.

The Conservatives

Opposing them were Conservatives who saw the church as one with the state. They valued tradition and the privileges of aristocracy. Apart from catholic cantons, they had a strong foothold even in Protestant city-states such as Basel, Neuchatel, and Geneva.

The confrontation of the opposing parties in cantons quickly evolved to the national level. To make it worse, it soon merged with religious issues. Ultimately, it was just because of the matters of religion that the nation slid into a civil war.

Old Faith vs. New Spirit

The influence of the Catholic church in the mountain cantons was enormous, especially among the rural population. In these areas, the church aggressively promoted the undisputed authority of the clergy.

Contrary to those, cantons with Protestant majority opposed everything the Catholic church endorsed. The liberalization of the society in these cantons implied the separation of state affairs from the church. The first step in doing so was the suppression of monasteries as bastions of Catholicism.

In 1840, monasteries and convents in cantons of Aargau and Soleure went so far in their aggressiveness that they organized and supported an armed rebellion against the liberal cantonal governments. The uprising aimed at government reforms that threatened the old faith however didn’t end well for those who spurred it. After it was quelled, the canton councils voted for monasteries and convents to be suppressed, thus eliminating the threat coming from these.

The Aargau rebellion, along with the unsuccessful 1839 conservatives’ putsch in the Zurich Canton, only intensified the division of the nation. Switzerland has become a country of Protestants versus Catholics, liberal radicals against conservative ultra-montanes.

The dispute between the two parties rose to tragic intensity in 1844. In May that year, another rebellion sparked by the Catholic church struck the canton of Vallais. Rebels from the mountain regions of the Upper Vallais, zealous Catholics, overthrew the liberal government of the canton and installed one to meet the wishes of the church. The people of the Lower Vallais organized the counter-insurgent movement but were utterly defeated at the Battle of Trient. The cruelty and disdain of the Catholics toward Protestants reflected in the decision of the Bishop of Sion to forbid his clergy to administer the sacraments to fallen enemy soldiers.

The canton of Lucerne, the centre of catholic action in Switzerland, actively supported the whole venture. Not only did the Lucerners assist in preparations of the rebellion, but their representatives in the Diet intentionally delayed the decision of other cantons to send the Confederation troops to restore the government. It was an act that Protestant cantons didn’t want to get over easily.

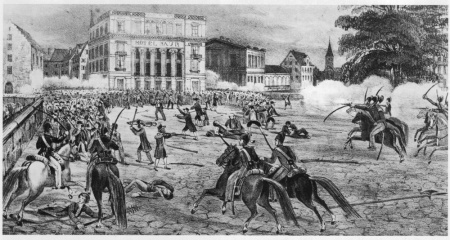

The Züriputsch 1839. Public Domain

Sonderbund

Lucerners were truly the bellwethers of Catholicism in Switzerland. Desperate to resist the wave of liberal reforms in the confederation, canton leaders were zealous in strengthening the foundations of old faith and conservative thinking. It was a process that asked for help from abroad and there certainly weren’t better men for the job than “God’s Marines”, the Vatican’s most faithful.

In 1844, the government of Lucerne invited Jesuits to take charge of religious education in the canton. Although the decision was backed up by the constitution of the confederacy, it threw liberals and radicals into a state of high alert.

Protestant cantons neighbouring Lucerne immediately gathered for action. A number of volunteer free-lances rallied against Lucerne in December 1844, determined to finish with ultramontane once and for all. Neither this, nor the expedition in April 1845, however, defeated the Catholics. Lucerners have already prepared themselves for defence and allied with neighbouring catholic cantons of Zug, Uri, and Unterwalden.

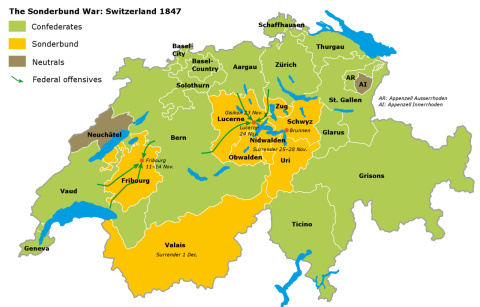

After the 1844/45 clashes, it became obvious that the quarrel between the two parties would not be settled peacefully. The first to close their ranks were Catholics. In 1845, cantons Lucerne, Fribourg, Unterwalden, Schwyz, Uri, Valais and Zug formed a Sonderbund - a “Separate League’’. The alliance of cantons established a joint war council and contacted France, Austria and Sardinia, powerful catholic states, asking for help. Their ultimate aim was to separate from liberal cantons.

Cantons led by liberal and radical governments responded by starting a campaign against the Sonderbund. After almost two years of lobbying, they secured a tight, one-vote majority in the Diet to declare the Catholic League illegal and call for the expulsion of Jesuits.

The dispute over matters of monasteries and religious education has now turned into a question of the very existence of the Swiss Confederation.

Map of the Sonderbund War in Switzerland 1847. by Marco Zanoli.CC BY-SA 3.0

The Most Polite War Ever

On November 4, 1847, the Diet issued a proclamation pointing out the reasons for the action. At the same time, they began military preparations by ordering a mobilization of the federal army. As commander-in-chief, they appointed General Guillaume Henri Dufour.

The Sonderbund cantons also mobilized their forces and began building fortifications, expecting the confederation troops to attack them. The unity in the ranks of the Sonderbund army was far from that of their enemies. The population of these cantons surely didn’t share the same enthusiasm for the faith as their leaders did. For that reason, Sonderbund relied on the intervention of foreign powers rather than on their own forces.

Fribourg

As soon as Dufour gathered an army of 94,000 men, he marched on Fribourg. As a veteran of Napoleon’s army, he devised a cunning plan to attack the isolated canton of Fribourg first. The city of Fribourg gathered around 23,000 men, of which, however, only 5,000 were experienced soldiers. Aware of their position, the commander of Fribourg, Francois Philippe de Maillardoz, planned to hold the Dufour’s forces long enough until the help from Lucerne arrived.

To his avail, there was not even a sign of reinforcements when Confederate troops invested the city on November 13. Instead of spilling unnecessary blood, Dufour sent a delegation to the city council with a call to surrender. After a 24-hour armistice was taken to consider the terms, citizens of Fribourg surrendered. Confederate troops entered the city, installed a provisional government, and expelled the Jesuits. Surprisingly, there have been almost no disorders or voices of complaint, not even by catholic clergy. It was certainly a proper response to Dufour’s decision not to retaliate against until-recent enemies.

It was an excellent decision for Defour to deal with Fribourg first, as the fall of the city caused the domino effect on the canton of Zug. On November 20, its council expressed a wish to lie down arms without even seeing a single Confederate soldier.

The surrender of Fribourg was a significant loss for the Sonderbund. They tried to respond by campaigning against the cantons of Zurich and Ticino, but with no success.The Campaign begun by the Confederate army was unstoppable. After Fribourg, they marched against Lucerne, the stronghold of Sonderbund. Dufour made an interesting approach by marching his troops along all five roads leading toward Lucerne. His intention was to show his full force and intimidate the entire population of the canton. Dufour hoped it might cause the defenders to surrender without a fight.

At the same time, he insisted confederate soldiers show no rancour and treat the defeated with kindness. Catholic churches were not to be attacked, and private property had to be respected at all costs. Durfour’s campaign was probably the most polite military action in the history of humankind. He knew very well that the common country of all cantons could not be built on bloodshed.

Bivouac of Confederate troops in the environs of Freiburg, 13 November 1847 - Public Domain

Lucerne

The Sonderbund army at Lucerne, led by General Johann Ulrich de Salis-Soglio, was, however, determined not to give in easily. Lucerners fortified the city and gathered a substantial number of men to confront confederates. City councilmen seemed to have had a gloomier view of the entire situation. When Confederates appeared, in the company of Jesuit priests, they departed the city in steamboats carrying with them the state chest with popular contributions.

Dufour was also certain that his number superiority would ultimately prevail. For this reason, he could afford to calculate in the battle. When Confederate troops appeared in front of Lucerne on November 22, Dufour decided not to attack the city walls. He knew that the battle at city gates could easily spark the combat fury among soldiers and disrupt his intentions to peacefully occupy the city.

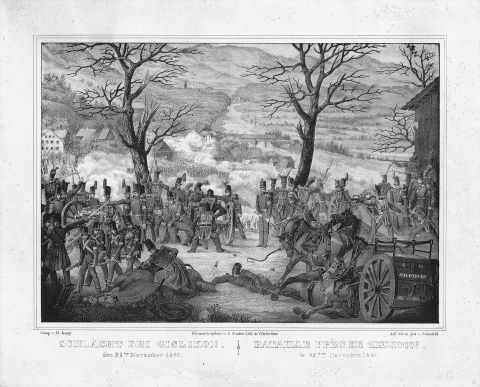

Instead, the main course of battle took place on November 23, on the opposite side of Lucerne, at the Bridge of Gisikon, where de Salis-Soglio posted powerful forces, supported by artillery. The battle lasted for six hours with both sides fighting vigorously. Ultimately, defenders succumbed to enemy’s number superiority and confederates gained control over the bridge. With the city surrounded, Sonderbundforces had no other choice but to surrender, even though there were still 20,000 soldiers within the city gates.

On November 24, Dufour and his men entered the city. The Fall of Lucerne practically meant the end of the war, as by November 27 all other cantons, members of the Sonderbund surrendered without a fight.

The Battle of Gisikon turned out to be the most violent battle of the entire war, with the total casualties of only 37 dead and only 100 wounded.

The Battle of Gisikon November 23, 1847 - Public Domain

The Rise of the New Age

In 1848, a peace settlement was signed, binding the Sonderbund cantons to pay 6 million francs of war damage compensation. That same year, the Diet, now unobstructed by conservatives, declared a new constitution. Switzerland became a federal state with cantons granted their sovereignty only as long as it didn’t impinge on the Federal Constitution.

The Battle of Gisikon, the last battle of the Sonderbund War, turned out to be the last battle that Swiss fought at all. After the civil war, the country entered a period of peace and prosperity that lasts until today.

Online sources

Sources/Further reading

- Duffield, W. B. The War of the Sonderbund. The English Historical Review, X(XL), Oxford. 1895, 675–698.

- Weaver, Ralph. Three Weeks in November: A Military History of the Swiss Civil War of 1847. Helion & Company, 2016.

- Church, Clive H., and Randolph Conrad Head. A Concise History of Switzerland. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Schelbert, Leo. Historical Dictionary of Switzerland. Scarecrow Press, 2007.