Table of Contents

Introduction

When Nazi Germany decided to attack the Soviet Union, the infamous operation Barbarossa, city of Leningrad (modern St. Petersburg) became one of three main targets of the offensive. It was an industrial hub, the base of the Soviet Baltic fleet, and held ideological and political importance as the birthplace of the revolution and former capital. However, the main goal set by Hitler wasn’t capturing the city, but rather destroying it along with its population. Thus, the stage was set for one of the deadliest clashes of World War II.

Cutting off the city from the Motherland

The encirclement and the start of troubles

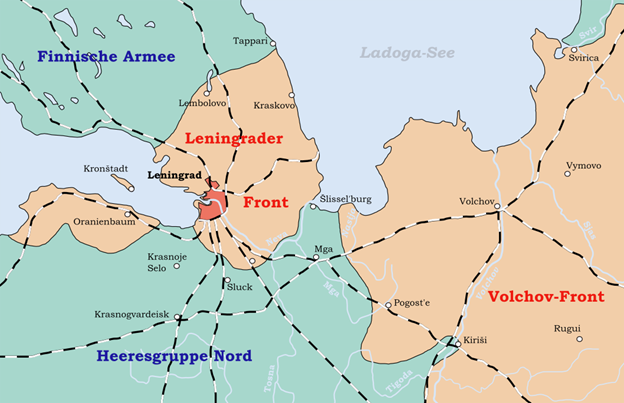

German advance began on June 22nd 1941, cutting through Soviet defenses with ease. By early August they were already closing into the city. In those days, city authorities employed its civilian population on fortifying their defenses, while thousands were evacuated. The unprepared Red Army could do little to hold the Wehrmacht, as by late August the Germans were already beginning the envelopment of the city. By August 31st, the last railway lines connecting Leningrad with the rest of the USSR were in German hands, while the Finns tightened the hoop, enclosing the city from the north. The supply of the city was already running thin but was finally cut on September 9th when the German armies reached the Ladoga lake east of the city. With that the siege officially began, setting a stage for death and destruction.

Map of German encirclement of Leningrad in September of 1941. Source

For the next almost 900 days the city and its population would become victims of a stubborn and merciless struggle between two armies. On one side, Hitler wanted to raze the city, along with its citizens, through bombardment and starvation. No surrender was to be accepted. On the other side, Stalin was determined to hold such an important ideological center. His order was to hold Leningrad at all cost. No capitulation was to be offered. Thus, the Siege of Leningrad was to become one of the darkest examples of total war in history.

Shelling and air raids

As the intended goal of the German assault was to destroy the city, Wehrmacht’s commanders felt no remorse for bombing Leningrad as much as possible. Initially, while their troops were still only approaching the old capital, these were mainly done through air raids. Those began in August, yet by early September Leningrad was in reach of German long-range artillery. The latter proved more troublesome for the civilians as no alarms or warning was possible, making it impossible to seek shelter in time. A small relief for the besieged citizens was the fact that by late September Germans transferred most of their air force to other parts of the front. Nonetheless, shelling continued, maintaining its tenacity up through to December. By then around 20,000 shells were fired from their guns, supplemented by thousands more from the remaining bomber squadrons. Physical destruction of the city continued throughout the siege with somewhat decreased tenacity, but bombardment once again exploded in 1943. The German command was by then venting its frustration with Soviet resoluteness to continue their struggle. Yet by then, the siege was coming to an end, thus it had less of an impact.

A street in Leningrad after German bombardment. Source

The German artillery and aircraft primarily targeted factories and fortifications, trying to break Leningrad’s defensive capabilities. However, they also hit civilian structures, sometimes accidentally but not so rarely with full intention. This caused widespread destruction of both residential buildings as well as schools, hospitals, and other public spaces. These also caused infrastructural damages to water and electricity systems, while of course causing civilian casualties. According to some estimates, bombardment killed around 6,000 Leningraders wounding 20,000 more. However, these numbers pale to comparison with casualties caused by starvation and freezing. Even the Leningraders felt that way. In the later stages of the siege, many refused to spend what little energy they had seeking shelter, rather tempting their fates.

Starvation, offenses, and salvation

Hunger and rations

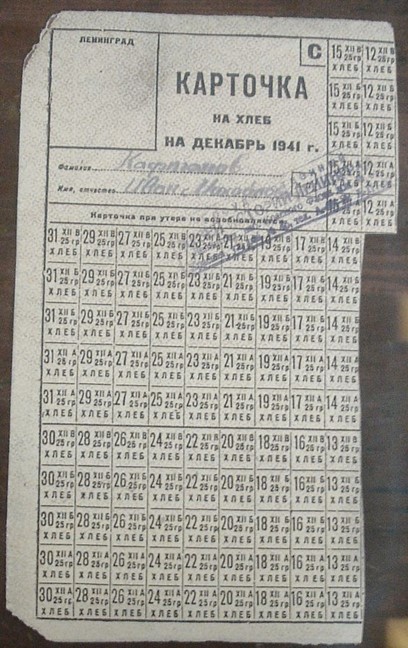

Soviet authorities realized early on that supplies were going to be an issue during the war. Thus, rationing was introduced in mid-July 1941. This proved to be instrumental, as it provided a sturdy system for Leningrad to endure its siege. Its population was split into four categories, with the first being working population people on active military duty, and similar important defensive roles. The second was the nonessential working population, then came unemployed and lastly children under the age of 12. Food was rationed based on this grade of importance, with initial daily bread provisions being fairly substantial. The first category was allotted 800 grams (28.2 ounces), nonessentials 600 grams (21.2 ounces), while unemployed and children were 400 grams (14.1 ounces). At this time, they were also rations of meat, cereals, and other foods, but those quickly run out.

Bread rationing stamp for daily provisions. Source

By the first days of September, when encirclement seemed unavoidable first reductions were made. Workers received 600 grams (21.2 ounces), white-collar employees 400 grams (14.1 ounces), and the latter two groups 300 grams (10.5 ounces). However, even with initial rationing, city authorities calculated they had between a month and two of food supplies. In just a few days, new lower actions were introduced, lowering bread provisions by 50 to 100 grams. Rations were further stretched by adding various additives to bread – cellulose, chaff, and sawdust were among the worst of them. Regardless, without proper resupplying the city would starve to death. Additional cuts were made throughout October, with the worst being introduced on November 20th, when frontline soldiers were given 500 grams (17.6 ounces) of bread per day, while rear-serving military members were allotted 300 grams (10.5 ounces). Hard laborers were receiving only 250 grams (8.8 ounces). The rest of the population were entitled to only 125 grams (4.4 ounces) of bread. Even so, city authorities calculated they had food for only a couple of days.

Road of life and death

By then people were already starving to death, often just collapsing in the streets. Simply put, 125 grams of bread gave about 300 calories while humans need roughly 2000-2500 calories a day. The Leningraders “supplemented” their diets with anything that seemed at least slightly nutritious. Boiled paper glue or leather strips were most common, while pretty much all pets were long gone. The only hope for survival was some form of resupply. During the initial months of the siege, the Soviet army tried supplying the city across the Ladoga but inadequate flotilla and German air force made resupplying far from sufficient. Even the start of the areal supply in mid-November wasn’t enough, as Luftwaffe still dominated the air. To make matters worse, the Germans also penetrated further east, jeopardizing supply lines towards the Ladoga as well.

Burying the dead during the Siege of Leningrad. Source

During November, winter weather caused the lake to slowly freeze, making it impassable for ships. However, by the end of the month, ice was thick enough for vehicles to ride across. The Soviet army quickly exploited this by creating a road into the city. It became the main supply line for Leningrad during the winter of 1941/42. For people in the city, it became known as the “Road of Life”, as it brought much-needed food, allowing them to survive. By mid-December Germans were pushed back a bit, liberating the supply chain towards the Ladoga and by 23rd rations were increased for the first time, though they remained low. As the supply systems were perfected and strengthened, further gradual increases came in early 1942. These transport lines were also used to evacuate more civilians, reducing how many mouths the city authorities had to feed.

Of course, the Wehrmacht tried to cut these supply lines as well, bombing the trucks, trying to break the ice, and destroy the makeshift road. These raids, mostly done from the air as well as numerous accidents gave this route another nickname. Those who drove on it called it the “Road of Death”. Despite that, it proved vital for the survival of the entire city.

Crime and atrocities

Despite the activity on the Road of Life, there weren’t enough supplies. People still had to manage on rather strict rations and diets, while shortages affected other aspects of lives. Most notable was the lack of fuel, both for machinery and for heating, as well as clothing and footwear. That kind of hardship of the besieged Leningrad proved to be a fertile ground for crime. Many reverted to stealing and scams, while attempts to defraud the system were more than common. The most desperate or immoral found murder as an agreeable tool in their survival. The very worst, famished and insane people regressed to cannibalism. At first, it was done to those already dead, but soon some of the cannibals began “hunting” for their prey. Others bought more than suspicious cuts of meat on the thriving black market.

At a certain point, no one seemed safe. Even the army patrols tended to move in groups. City authorities quickly realized that if the city was to survive, both morally and physically, severe actions were required. A harsh martial law was introduced, allowing the army patrols to execute on sight for any committed crime. The order had to be maintained or chaos would bring Leningrad down. Regardless, the city remained in chaos throughout the siege.

Liberation and a final tally

Blockade broken

Besides suffering from the lack of supplies and thriving crime, the Leningraders were continuously engulfed in fighting. Military actions continued on both sides, with the Red Army trying to break the siege and the Wehrmacht trying to both deflect those attempts and put additional pressure on the city. The line between the front lines and the home front was blurred if not nonexistent. The fighting was somewhat sporadic throughout most of 1942, but an important advance was made by the Soviets in January of 1943 when they managed to create a retake a narrow corridor along the coast of Ladoga. On January 18th total blockade was lifted and the first railway connection was reestablished in February.

Nevertheless, the Germans were still threatening the city, keeping it partially besieged, continuously trying to disrupt the Soviet supply lines. Life in the city started to improve as rations increased and consumer goods began to flood in, while the enemy bombardment once again gained in tenacity. Nevertheless, the city remained in continued imminent danger both from German attacks and renewed blockade. Yet by the late 1943 and early 1944, the Soviets at last executed the final push, officially liberating the city on January 27th. With that, the Siege of Leningrad ended after 871 grueling days.

A ghost city

As the Germans were being chased away from the Soviet territory, the city sighed with relief. However, then came time for accessing the damage and counting the dead. Leningrad suffered notable damage from bombardment, yet buildings were easy to rebuild. The truly staggering cost came in human lives lost. Initially, the Soviet government estimated 650,000 civilian deaths, using that figure during the Nuremberg Trials. However, these estimates were quickly dismissed as inaccurate, mostly due to fallible Soviet bureaucracy. Modern estimates usually hover between 800,000 and 1 million civilian casualties. That estimate puts Leningrad’s casualties roughly the same, or even slightly higher than the entire World War II losses of the US and UK combined. When the military casualties are added, the Soviet losses during the siege jump to about 1,5 million people.

In the end, the city survived, though it remained a mere shell of its former self. By the end of the siege, only about 600,000 citizens remained, as throughout the siege more than 1 million were evacuated. Leningrad lost 2/3rd of its population, scarred all over. The stubborn defense it put up prompted the leaders of the USSR to give the entire city an honorary title of “Hero City”, comparable with the highest personal distinction “Hero of the Soviet Union”. Nevertheless, such accolades echo with triviality in the face of thousands of lost souls.

Remembering the dead

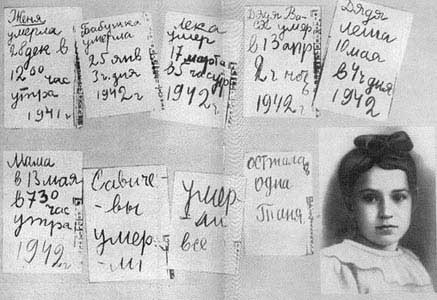

When talking about Leningrad, as well as other major battles and wars, we tend to glorify them as heroic or romanticize them as just or astounding, losing the perspective of lost lives. However, it is vital to paint a picture of how gruesome and vile war can get, especially when looking at it from the eyes of an innocent individual. For Leningrad, a short and perfect commemoration is a simple quote of a “death diary”, written by Tanya Savicheva, a young girl who lived through the siege:

Zhenya died on December 28th at 12 noon, 1941. Grandma died on the 25th of January at 3 o’clock, 1942. Leka died on March 17th, 1942, at 5 o’clock in the morning, 1942. Uncle Vasya died on April 13th at 2 o’clock in the morning, 1942. Uncle Lesha May 10th, at 4 o’clock in the afternoon, 1942. Mama on May 13th at 7:30 in the morning, 1942. The Savichevs are dead. Everyone is dead. Only Tanya is left.

Tanya Savicheva and pages from her diary, used as evidence at Nuremberg Trials. Source

Eventually, Tanya died as well, succumbing to the effects of the siege in the summer of 1944, at the age of 14, once again reuniting with her family, neighbors, and the other deceased Leningraders.

Sources

- Wiki Siege of Leningrad

- Britannica - Siege of Leningrad

- Siege of Leningrad begins

- The city that refused to starve in WWII

- Only skeletons, not people

Further reading

- Albert Pleysier, Frozen Tears: The Blockade and Battle of Leningrad, University Press of America, 2008.

- Anna Reid, Leningrad: The Epic Siege of World War II, 1941–1944, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011.

- David Glantz, The Siege of Leningrad 1941–44: 900 Days of Terror, Zenith Press, 2001.

- John Barber and Andrei Dzeniskevich, Life and Death in Besieged Leningrad 1941–44, Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- Constantine Krypton, The Siege of Leningrad, the Russian Review, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Oct., 1954), pp. 255-265.

- Daniil Alexandrovich Granin, Leningrad Under Siege, Pen and Sword Books, 2007.

- Harrison Evans Salisbury, The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad, Da Capo Press, 1969.

- Alexander Werth, Leningrad 1943: Inside a city under siege, I.B. Tauris, 2015.

- Robert Forczyk, LENINGRAD 1941-44 - The epic siege, Osprey, 2009.