Table of Contents

Introduction

It is hard to pinpoint the exact date when the Cold War began, as it was a gradual transition from wartime allies to peacetime opponents. Yet, the tensions and troubles on the horizon were clear from the get-go, maybe most picturesquely described by Sir Winston Churchill. In March 1946 he described a division of Europe by saying “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent”. Nevertheless, such a gloomy depiction of the Cold War affairs remained nothing more than a metaphor until August of 1961 and the construction of the Berlin Wall, which became its most symbolic representation.

Erecting the barricade

Creating a physical divider

After World War II ended, Germany and its capital were divided into four occupation zones between France, Britain, the US, and the USSR. However, it wasn’t long before the difference in the approach to the German issue became apparent. On one side, the Soviets wanted to make them pay for the 20 million dead they lost, imposing harsh rule and reparations. On the other hand, the rest of the allies leaned towards a more lenient approach, though not without reparations of their own. Yet, the western powers quickly realized that they needed Germans to be economically self-sufficient and with some sense of dignity left, as they were indeed the barrier against the spread of communism, a growing threat in their minds. As such, they began investing in it through the Marshall Plan, while organizing their occupation zones into a single entity.

This angered the Soviets who then put Berlin into a blockade from July 1948 to May 1949, trying to prevent such a development. The blockade failed as the western power managed to supply the city from the air, but it ended with the creation of West Germany (Federal Republic of Germany). The Soviets responded by creating East Germany (German Democratic Republic). With that new borders were created, yet those remained loose. Nevertheless, the two Germanies quickly became polar opposites. The West was enjoying an economic rebirth and numerous liberties, while the East was heavily oppressed by the Soviets and their puppet regime. As such, thousands began fleeing to the West, causing the GDR to close up their western borders in 1952, erecting numerous obstacles along its lines.

In the following years, that border was reinforced with miles and miles of fences, barbed wire, ditches, even minefields. Nevertheless, thousands of East Germans managed to cross to the west, causing the GDR to lose roughly 2 million citizens by 1960. By then, the last “hole” in the border was in Berlin, which remained only lightly guarded. Khrushchev tried to negotiate around this problem with Kennedy in Jun 1961 but failed. Having no other alternatives left, the Soviets and their East German allies proceeded with their plan to close the last unguarded part of the border by erecting a wall around West Berlin.

From a fence to a wall

The construction began on August 13th 1961, with about 20,000 East German and Soviet soldiers working on it. As the 155km of West Berlin’s city boundaries to the GDR were closed since 1952, the remaining 43km that ran within the city limits were barricaded rather quickly. Despite being called a wall, at that point the barrier was more of a fence, comprising barbed wire spread between wooden and concrete posts. However, by August 17th the first improvised walls began to emerge, made from bricks and concrete blocks. Along the way guard posts, wooden towers, and similar additional structures were added, yet the wall remained rather shoddily constructed.

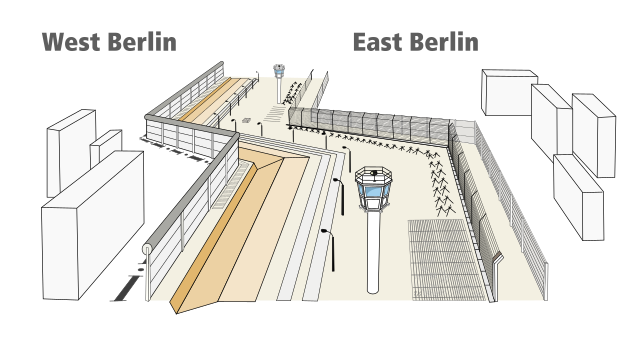

A diagram of the 4th generation Berlin Wall with all its defenses.

These hastily mashed barriers were replaced in 1962, when entire blocks of buildings were demolished to create a 30-100m clear area guarded by two walls on each side. Where it was possible, older walls were replaced by premade concrete panels. The wall itself was topped with barbed wire and spikes, while at certain areas anti-vehicle ditches and hedgehogs provided an additional layer of “protection”. Searchlights, towers, and constant patrols were also part of the Berlin Wall. By 1965 parts of the wall were once again improved with newer concrete blocks, fences, chain-links, while the wall itself was topped with a gripless sewer pipe, making climbing over mostly impossible.

In 1976, the Berlin Wall was once again improved, with even larger and more robust concrete pre-made panels. It was a more durable barrier, topped once again with even thicker gripless pipes. New towers were also added, and certain border areas expanded. Additional lights, barbed wire, anti-vehicle, and anti-personnel traps were also added, alongside an electronic-sensor signal fence at critical areas. However, by the 1980s there were still parts of the Berlin Wall from the 3rd or even 2nd generation, as improvements were implemented only at vital positions. Nevertheless, it was a formidable barrier stretching for more than 150km, with walls reaching heights between 3.4 and 4.2 meters, guarded by more than 180 towers and thousands of soldiers.

The functionality of the Berlin Wall

Purpose of the wall

When the East German government began building the Berlin Wall, it offered a plethora of explanations to its citizens and the rest of the world. A common theme was protection from the west, for example, dissuading an invasion from the west or preventing enemy agents from entering the communist realm. Sometimes they claimed such a decision was economically driven, as supposedly the westerners would buy state-subsidized goods in East Berlin. Of course, neither the west nor east truly believed in these excuses, as it was clear that the barricades were positioned to prevent people from exiting from East Germany, not entering it. This was even more clear when it came to travel restrictions, which rarely prevented the westerners from entering East Berlin.

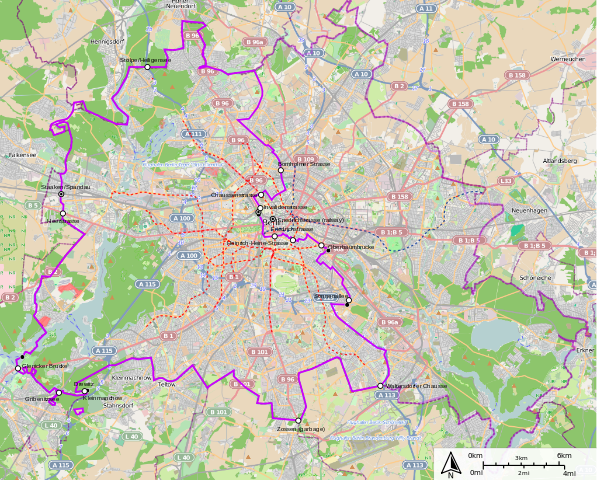

A map representing division between East and West Berlin, with a bright purple line representing the Berlin Wall.

In reality, the Berlin Wall was placed to finish sealing off East Germany from FDR. By 1961 the exodus of its population became too much of an issue to ignore, especially as most of the emigrants were young and educated people, those who were supposed to be the future of the nation. Thus, the so-called “brain drain” had to be clogged. Yet, even such explanations fail to grasp the larger picture – the wall itself, as well as the closing of the rest of the border, was supposed to bring stability to a communist regime that was shaken by being in too close contact with the capitalist west.

Fulfilling its objective

In regards to all that has been said about the purpose of the Berlin Wall, it fulfilled all of its objectives. It did prove an additional hurdle for western spy activity and it lowered the volume of visitors from West Germany. Furthermore, it eased the tension in the west, as walling off West Berlin meant the Soviets abandoned the idea of conquering it. Thus, in a rather indirect way, it did slightly lower the chances of “heating up” of the Cold War. However, its most notable success was in the realm of cutting off the migration flow to the west. For just over a quarter of a century, about 5000 people managed to illegally cross the wall and defect to the west. Compared to tens of thousands on a yearly scale before 1961, it proved to be quite effective. Similar success was achieved on other German borders, improving throughout the years. Thus, from August 1961 to the end of 1962, just 14 thousand people crossed into West Germany. By the 1970s, this number dropped below 1000, while in 1985 it fell as low as 160.

The Berlin Wall also succeeded in its grander goal, as the communist rule in East Germany strengthened. The wall provided a point of focus and coherence for the Party faithful while adding another layer of control of the masses in an area especially fragile as divided Berlin was. It also served as a training and gathering point of loyal governmental forces, as the guards became one of the bastions of the regime.

Tearing down the wall

Failing through success

Despite fulfilling its purpose on most of the levels, the Berlin Wall was ultimately a major failure on part of the entire eastern bloc. Its visual appearance was reminiscent of prison walls, and despite what party officials claimed, everyone knew its main goal was to keep people in, not out. Thus, the mere existence of the Berlin Wall posed a question of communist rule legitimacy. How good a regime could be if it had to force its own people to stay under it? With that, the wall became a picturesque example of everything wrong with the entire eastern bloc and ruling communist ideologies. In the long run, it proved too damaging from the propaganda and ideological perspective.

Its image was only worsened by the fact that it’s guards were allowed to shoot any trespassers. It is estimated that around 200 people, if not more, were killed during their attempts to cross the wall. Such images added to the grim impression of the Berlin Wall. To make matters worse for the East German government, it wasn’t a cheap project, especially for a country that wasn’t experiencing any type of economic prosperity. Some estimates go up to 500 million East German marks per year for maintaining and upgrading the wall. In perspective, a loaf of bread was about 1 mark. Thus, it put additional strain on the already ineffective economy.

End of division – end of an era

Although the Berlin Wall brought stability to East Germany, by the late 1980s the state began to lose its grip. This was facilitated by the fact that the Soviets were retreating inward, allowing more freedom to other communist regimes. Without their support, local parties across east Europe began to falter. Similarly, the GDR regime felt internal shocks. As older party cadres were replaced with more liberal leaders, the population began to voice its dissatisfaction. Unable to control them any longer, the Berlin Wall fell on November 9th 1989, with its guards acting like mere spectators. In the end, the wall was as stable as the government that built it. Within a year, Germany was unified once again, erasing the need for any kind of borders or barricades with Berlin. As the division was being erased, the Cold War was coming to an end.

Berliners atop the wall in November of 1989.

The Berlin Wall was dismantled, though a part was kept as a memorial, while its route was marked along some of the streets and parks. Pieces of it were sent to various museums and other cultural institutions. Nevertheless, the wall remains a vivid symbol of the Cold War, exemplifying both a division of the world as well as the rather despotic nature of most communist regimes. As such, the Berlin Wall became a victim of its own success. We can only hope never arises anywhere in the world, as our politicians should learn that building walls rarely really solve any underlying issues that may necessitate them.

Sources/Further reading

- Gordon L. Rottman, The Berlin Wall and the Intra-German Border 1961-89, Osprey Publishing, 2008.

- Patrick Major, Behind the Berlin Wall: East Germany and the frontiers of power, Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Frederick Taylor, The Berlin Wall - A World Divided 1961-1989, HarperCollins, 2007. Buch, C. M., & Toubal, F. (2009), Openness and growth: The long shadow of the Berlin Wall, Journal of Macroeconomics, 31(3), 409–422.

- W.R. Smyser, Kennedy and the Berlin Wall: “a hell of a lot better than a war”, Rowman & Littlefield, 2009.

- Ann Tusa, The last division – Berlin, the wall and the Cold War, Skyhorse Publishing 1997.

- Julia Sonnevend, Stories Without Borders - The Berlin Wall and the Making of a Global Iconic Event, Oxford University Press, 2016.

- John P. S. Gearson and Kori Schake, The Berlin Wall crisis: perspectives on Cold War alliances, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Christopher Hilton, After the Berlin Wall – Putting two Germanies back together, The History Press, 2009.

- Stein, M. B. (1989), The Politics of Humor: The Berlin Wall in Jokes and Graffiti, Western Folklore, 48(2), 85.

- Drechsel, B. (2010), The Berlin Wall from a visual perspective: comments on the construction of a political media icon, Visual Communication, 9(1), 3–24.

- Paul Ganster and David E. Lorey, Borders and Border politics in a globalizing world, SR Books, 2005.