Table of Contents

Looking at the modern history of China, for most westerners, there was an image of a weak and chaotic empire in the Far East, one in which glory days were long gone. In their view, the Chinese were a second-rate nation ripe for plunder, a perfect target for 19th-century imperialism. Nevertheless, China managed to avoid being colonized, despite being beaten in two conflicts, today known as the Opium Wars. That brings the question of how did Beijing manage to preserve its independence and what was the importance of the Opium Wars?

The first clash with the west

Rising tensions

Despite having a long and prosperous history, the Qing dynasty China in the late 18th and early 19th century was long past its glory days, especially when compared with the rising industrial power of European nations. Nevertheless, it was still commanded some respect and economic stability. Most importantly, China managed to retain a positive trade balance with the westerners as oriental commodities were all the rage in Europe. As such, China primarily exported its silk, porcelain, and tea, receiving notable amounts of silver in return. Despite that, the Chinese remained quite wary of foreign influences and possible exploitation, causing them to set up the so-called Canton System of trade, where basically all foreign traders were limited in operating in a single harbor - Canton (modern-day Guangzhou). Furthermore, non-merchant contact between the local population and European traders was banned.

A painting depicting foreign merchant depots in 19th century Canton.Wikipedia

Of course, trade disbalance irritated their European partners, most notably the British whose monopoly over maritime trade expanded from the late 1700s. They found that selling opium was a profitable way to restore the trade equilibrium, and slowly began increasing their opium production in India. By the late 18th century, Chinese officials recognized that there was a rising drug addiction problem in their country and they outlawed the opium trade. However, this didn’t stop the British who were joined by the Americans in the illicit narcotics trade. That only brought down the prices and widened the opium usage, prompting the Chinese imperial government to act. By the late 1830s, the Chinese began a crackdown on opium smuggling, confiscating and destroying large quantities of the drug, even the stockpiles belonging to foreign traders.

Small war and large consequences

At first, the Chinese war on drugs caused only smaller clashes with the British traders, which caused outrage in Britain. A reaction was demanded, although many were openly against the opium trade. Under pressure from various merchants and manufacturers, British Parliament buckled and decided to support a punitive expedition against the Chinese led by the East India Company. The war officially began in September of 1839, though the British offensive commenced in the summer of 1840. Over the next two years, the conflict was fought almost one-sidedly. The superior British navy sailed along the Chinese coastline, venturing into large rivers, capturing numerous harbors and coastal forts. The Qing government, with its outdated technology and an empty treasury, had only numerical superiority which proved to be futile. After several losses and facing chaos, the Beijing government was forced to sue for peace in August of 1842.

The Treaty of Nanjing officially ended the First Opium War. First of all, the British demanded the further opening of China to their traders. The British gained access to additional 4 ports, including Shanghai, where their consuls could directly contact local Chinese authorities. Furthermore, taxation of the trade was no longer solely under Chinese jurisdiction but was to be agreed upon between the British and the Qing officials. Additionally, the Chinese had to pay some war indemnities and reparations for lost British economic losses caused by the war. However, the most long-lasting consequence of what was essentially a small conflict was the cession of Hong Kong Island to Britain. As a crown colony, Hong Kong became the center of British influence and power in the region, an important imperialistic foothold in Asia.

Chinese infantry with outdated matchlocks fighting British armed with the muzzle-loading rifle during the First Opium War. Wikipedia

The futility of Chinese resistance

Imperialism on the hunt

In the end, the Nanjing Treaty failed to bring any conclusion to the existing issues. Opium trade wasn’t covered by it and it remained a thorn in the eyes of the Chinese government. On the other hand, the British weren’t satisfied with how the trade and diplomatic relations developed afterward. An additional issue was that western imperialism was on the rise during the mid-19th century, only increasing its appetites in China. Finally, the ease of British victories showed other colonial powers how weak was the Qing dynasty, with a similar effect to the unsatisfied Chinese subjects. For the westerners, this meant all major powers, including Russia, France, and the United States signed their separate treaties with China, opening its ports to their merchants. Furthermore, in 1843 Britain negotiated extraterritoriality of its subjects in China as well as a most favored nation status. All the while, the Qing government faced several uprisings, most notably the Taiping Rebellion, further weakening China.

Unsatisfied and very aware of Chinese vulnerability, Britain unsuccessfully tried to renegotiate its trade agreement with the Qing. Impatience grew among the British, with a growing warmongering fraction in London. Thus, by 1856 British officials in Hong Kong were more or less looking for a fight. Unfortunately, for the Chinese, a reason for hostilities was given in October when Canton officials boarded a ship with a Chinese crew that was suspected of piracy, but which sailed under a British captain and flag. In other circumstances, that would be a relatively benign incident, but the British were resolved for more. After local Canton officials failed to satisfy British demands, they began the naval bombardment of the city. Hence, the Second Opium War began without the expressed consent of the British Parliament.

Circling of the vultures

Like in the previous confrontation, China stood no chance on the battlefield. Its armies were by then even more outdated, while also struggling against several ongoing uprisings. Nevertheless, the British asked other western states to join them in an alliance, partially because they were facing a rebellion in India. Only France accepted, and two European power began their joint operations by late 1857. Russia and the United States officially declined but remained involved. The US navy assisted the Anglo-French allies in several battles despite supposed neutrality, while Russia sent its envoys for diplomatic machinations behind the scenes, staying in contact with both the Qing and the European allies.

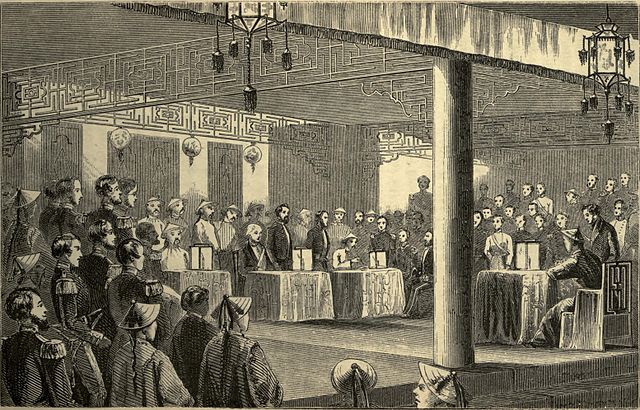

The fighting was even more one-sided than in the previous clash, with several European victories before their punitive expedition sailed towards Beijing in the spring of 1858. This alarmed the Qing emperor who agreed to a peace negotiation. The talks were held in Tianjin, where besides the belligerents, the US and Russian representatives were also present. By June China signed the Tianjin Treaties with all four western powers. This agreement opened up 10 more ports for trade, allowed the westerners to travel across China freely, and opened the Yangtze River for foreign vessels. Furthermore, Beijing was forbidden from persecuting Christians and forced to allow permanent embassies to all four western nations. There were other less important points, but overall it was seen as a disgrace for the Chinese imperial court.

An illustration depicting signing of the Tianjin Treaties. Wikipedia

Subjugating China

For a while, hostilities subsided, yet the Qing dynasty proved to be somewhat sluggish and unwilling to fulfill the Tianjin Treaties. Most notably, the imperial court put up a stiff resistance towards the issue of foreign embassies in Beijing, a city long out of reach for outsiders. A part of the Chinese government wanted another attempt to fight off the westerners. The Anglo-French allies were happy to oblige them. By mid-1859 hostilities resumed, but even larger forces as now both sides prepared for a conflict. The Chinese forces put up a much stiffer resistance, even prompting the Americans to intervene to help their British “brethren”, repelling their initial attack However, by the summer of 1860 Britain had resolved the rebellion in India, amassing a much larger force. In August, the allied forces broke through the Chinese coast defenses near Beijing and moved towards the city.

Negotiation attempts were made by both sides, but those failed because of mutual distrust as well as diplomatic and cultural differences. Those failures only worsened the relations. The Anglo-French allies arrived outside the Chinese capital, while the emperor fled further inland. They wanted to force the Qing government to accept their conditions, thus decided to burn the imperial Summer Palace. The occupation of Beijing and the destruction of the Forbidden City were discussed, but the Europeans knew it would be too much of a disgrace for the emperor. In the end, the destruction of the Summer Palace proved to be enough as by mid-October 1860 China signed its capitulation.

Consequences of defeat

Immediate ramifications

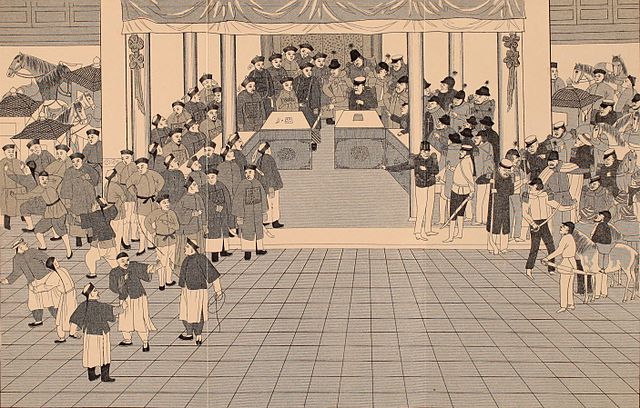

The Qing representative was given to sign the peace treaty, known as Convention or Diktat of Beijing, with France and Britain, as well as with Russia who also had its representative present. It reaffirmed the Tianjin Treaties, including the agreement China signed with the US, but also greatly expanded on them. Tianjin was transformed into an open port as well, while it also allowed the British to transport indentured Chinese laborers to the Americas. The Qing dynasty was forced to pay a larger indemnity, while also forcing freedom of religion in China. Additionally, the opium trade was de facto legalized. However, the most important clauses were cessions of Kowloon, territory across the Hong Kong Island to the British and of what is now known as Primorsky Krai, large territory north of the Amur River and east of the Ussuri River, to Russia.

A Chinese painting depicting Signing of the Convention of Beijing. Wikipedia

Such unfavorable peace signaled to the rest of the imperialist forces that China, once a mighty empire, was now down on its knees. It led to even more of the so-called unequal treaties signed by China with other nations at its own expense. Some were forced on Beijing by the same western powers that defeated it in the Opium Wars, but many others joined in like for example Portugal, Netherlands, and Prussia (later Germany). Even Japan managed to impose its will in 1895. Of course, such a weakened image and power of the Qing government only further destabilized China, slowly leading the nation into chaos, with even more rebellions and the rise of local despots who largely ignored the central government. All the while, the Chinese economy suffered, as the Qing regime was unable to protect it from foreign exploitation. Even worse, opium addiction grew along with the import of the drug, while the hands of the Chinese government were tied.

Long-lasting implications

However, focusing on these direct consequences of the Opium Wars obscures much more important effects on China and the world. On one hand, the harsh treatment and mistreatment of the Chinese people by the various foreigners only deepened existing mistrust and dislike of other nations. It remodeled Chinese nationalism towards a more strikingly xenophobic disposition, with a discerning hatred towards nations that humiliated and abused the Chinese people. All the while, the economic ruin and public degradation from opium abuse made China a fertile ground for social unrest, paving the way for the communist revolution. Furthermore, it was at least partially due to the Opium Wars that anti-imperialism paroles became one of the staples of the communist regime in China after 1949.

Additionally, the losses in these conflicts confronted the Chinese with the fact that despite their dislike of the westerners, they had to learn from them. After the Opium Wars, there were constant attempts to modernize the Chinese society, economy, and military. These proved to be largely unsuccessful, at least before the Communist Party managed to ring back some order to the nation, leading to an enormous economic leap of the recent decades.

A caricature depicting China as a wounded dragon being attacked by various imperialistic nations. warfighterjournal

Nevertheless, the trauma caused by the Opium Wars, symbolizing national disgrace and humiliation persist. The severity of how the Chinese independence was abridged in the late 19th century continues to be an embarrassing reminder of China’s past defeat and imperialistic encroachment, as well as of the West’s self-righteous hypocrisy and hubris. These issues continue to plague even the modern relations between China and the old powers. Specific examples can be found in the Sino-Soviet Split, where Beijing continuously attacked Moscow on the fact that the Soviet regime kept the territories its imperial forefathers took from the Chinese. Even more recent was the issue of Hong Kong, which still remains split between Chinese control and the legacy of British rule, despite formally being returned to China in 1997. It is a political issue of the contemporary era, built upon the consequences of the 19th century Opium Wars.

In the end, the importance of the Opium Wars lies in how it transformed China, its society, and its outlook on the world. It ripped it out of its remnants of medieval feudal phantasmagoria and trusted it into the reality of modernity, one in which China was on the bottom of the international hierarchy. Even today, the Chinese are still trying to heal their scars as they climbed back to the top, determined not to let such humiliation happen to them again.