Table of Contents

After the United States faced defeat in the Vietnam War it seemed like both Cold War superpowers learned their lesson - do not interfere in unnecessary conflicts, especially when those are a civil war. However, in late 1979 the USSR repeated the American mistake, leading to the Soviet debacle in Afghanistan that would end in a defeat nearly a decade later. What went wrong and why is it sometimes considered a greater failure than Vietnam?

Descending into quagmire

Friendly neighbors

For a substantial part of Afghan history, it was a target of mighty empires around it. Among many others, imperial Russia also had its eye on it. Yet, it could never conquer it because of the so-called Great Game with Britain about the control of the region. Thus by the early 20th century, Afghanistan became a buffer state between two imperialistic European powers. Later, the new Soviet regime accepted that notion, keeping relatively friendly relations with the Afghan neighbors. These ties became tighter in the ’50s when the USSR began giving financial aid to economically struggling Afghanistan. However, the situation remained dire, prompting a coup in 1973. The new regime abolished the monarchy, proclaiming the Republic of Afghanistan.

Despite that, Afghani reforms proved unsuccessful in all spheres, creating instability in the nation. Finally, that prompted the Peoples Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), formed in the mid-60s under Soviet influence, to stage yet another coup. Marxist-Leninist regime took over in early 1978, renaming the state the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. With a new ideologically close regime on its borders, the Soviets rushed to support it, sending even more financial aid. However, the PDPA proved to be rather insensitive in implementing its leftist reforms, provoking riots and violent insurrections. This created a cycle of violence and counter-violence, where Afghanistan was slowly descending into chaos.

An image of Afghani revolutionaries in the streets. from bbc.co.uk

Allied intervention or invasion

As the situation in Afghanistan worsening, in the spring of 1979 the PDPA leaders appealed to the Soviets for military help. However, the USSR leadership remained skeptical about its direct involvement. Its initial move was to give military equipment and experts, hoping the PDPA would be able to take care of insurgents on their own. Things started to complicate even more as the Afghan communist regime split between two leaders. On one side was a Soviet protégé Nur Muhammad Taraki, and Hafizullah Amin whom the KGB suspected with tie to CIA. Though the claim for Amin was never confirmed, the issue became was brought to a boiling point in September when Amin killed Taraki, taking sole control of the nation.

For the Soviets, this was a red flag. They worried that Amin would slowly drift towards the US, which was seeking a new ally in the region after they lost Iran in the Islamic Revolution in 1978. Furthermore, that same revolution also brought Islamic fervor in the region, creating concerns in the Kremlin that if the PDPA regime were to fall to a similar force, it would cause unrest in the Muslim Soviet republics. Regardless, the Soviet leadership still wanted to avoid direct involvement, rightfully judging it would be damaging to the USSR’s global interests. They tried to reign in Amin, playing with party politics of PDPA. Nevertheless, from October, Kremlin began searching for other options, including military invasion.

By December, it was clear that Amin wasn’t going to play the role Soviets imagined for him, while his even bloodier repressions of the insurgents led to nationwide revolt. He had undisputed control of just 20% of Afghanistan. Kremlin, led by Leonid Brezhnev, finally decided to take the gamble with an armed intervention that began 24th December 1979. While most of the world deemed it an invasion of a sovereign nation, the Soviets claimed they were acting upon a request of the Afghan government to honor the friendship treaty signed between the two nations in 1978.

The Soviet-Afghan War or Soviet Vietnam

Early phases of the war

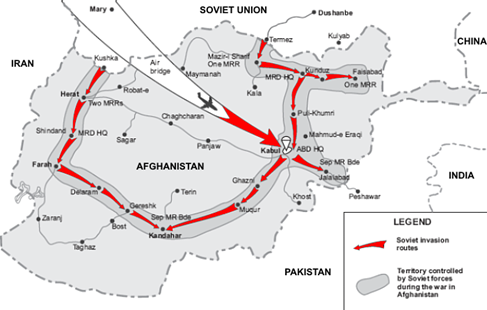

While the politics and diplomacy were failing, Soviet army experts began planning for an invasion. The basic idea was to seize strategically logistically important locations and take hold of Afghanistan, then to slowly strengthen PDPA forces, allowing their regime to stabilize. It was supposed to be a quick intervention, akin to those in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. Interestingly, the Red Army officers stationed in Afghanistan as experts warned their government that such actions wouldn’t go as easily as they planned. Their opinions were that Afghans were notorious for their struggle against foreign troops and that they would force the Soviet army into much more involved actions and combat. Furthermore, the geography of Afghanistan was perfect for guerilla warfare and notoriously hard to put under forceful control. Nevertheless, their pleads were ominously ignored and they were relieved from their posts.

A map of Soviet invasion routes. from wiki commons

The initial invasion went according to plan, with about 50,000 Red Army soldiers advancing south through two land routes and an aerial corridor to Kabul. Afghan army put up no resistance, Amin was deposed and executed, and a new government was formed under Babrak Karmal. However, within days the Soviet rose-colored glasses were crushed. Instead of being seen as liberators from Amin’s oppressive rule, the Red Army was seen as occupiers, stirring up Afghani national feelings, while the Afghani army proved inadequate for any serious duty. Thus, the Soviets were slowly drawn into a serious conflict with the resistance fighter, notorious Mujahideen. After few weeks of open resistance, the Afghani resistance reverted to their traditional guerilla tactics, retreating to the mountains. The Soviet-Afghan War became a deadlock, as the Soviets couldn’t wrestle the countryside from the Mujahideen, while they were unable to confront the Red Army in the cities and on the open.

Senseless operations and international interference

By the mid-1980, the Soviet-Afghan War settled into largely pointless actions on both sides. The Red Army continuously attempted to locate and eliminate the Mujahideen strongholds, which were scattered across Afghanistan. Some of these were large-scale offensives, but smaller and localized actions were also implemented. In response, the resistance forces used classical guerilla tactics, ambushing Soviet supply convoys and smaller units, while also laying down various traps and mines. While both sides achieved short-term and marginal victories, neither was able to achieve any specific gains. This forced the Kremlin to slowly increase its military presence, which peaked at about 110,000 soldiers, yet even that proved futile.

A group of Mujahideen solders taken in 1987. from wiki commons

All the while, the Mujahideen forces also increased, as more and more Afghanis flocked to help them fight the invaders. Thus, from modest 40,000 men, their numbers rose to estimated 200-250,000 fighters. More important than that, they began receiving significant foreign aid. While the resistance received modest and mostly outdated weapons from the US before the invasion, partially adding to Soviet paranoia about their influence in Afghanistan, in the following months and years these increased in number and sophistication. Another important ally of the Mujahideen was China, as it was in confrontation with the Soviets in the so-called Sino-Soviet split. Finally, the Afghani rebels could also count on Pakistan for not only military aid, but their territory sometimes served as hiding grounds for their forces and a supply route used by the Americans. Thus, in a stretch of a comparison, it acted in a similar role that Laos and Cambodia played in the Vietnam War. The Soviets even bombed supposed Mujahideen garrisons in Pakistan.

Nothing to do but to get out

After roughly 5 years of deployment, it became increasingly obvious the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan was an exercise in futility. Things began to change in early 1985 with the arrival of Mikhail Gorbachev at the helm of the USSR. He immediately began dealing with Soviet entanglement through political and diplomatic means, but also through a change of military tactics. The bulk of the fighting was to be passed on to the Afghan regular army. It was officially some 300,000 strong, but in reality much smaller due to desertion and ineffectiveness. The Red Army would provide crucial artillery and areal support to them. Furthermore, the Soviets focused more on the actions of their special forces, the infamous Spetsnaz. As the war reached the peak of engaged units and the ferocity increased, late 1985 and early 1986 became the bloodiest moments of the conflict.

Soviet troops in action during the Soviet-Afghan War. from bbc.co.uk

All that was done to increase the stability of the PDPA government, including Karmal’s removal and of appointing Mohammad Najibullah in April of 1986. Najibullah launched the campaign of “national reconciliation”, while the Soviets began to execute a slow withdrawal. The Red Army relied even more on artillery and bombardment, while their officer avoided men-to-men combat as much as possible. This was important for Kremlin to save what was left of Soviet reputation, as a rushed exit would mean complete defeat. The withdrawal was officially announced in mid-1987, but the Red Army engaged in one last grand offensive later in the year. It was successful, but once again pointless, as it didn’t bring any significant military or political gains.

By mid-1988, Soviet presence was cut by half, while the government and Mujahideen continued to clash. On February 15th 1989, the last Soviet regiment left Afghanistan, officially ending the Soviet-Afghan War. The PDPA regime managed to hold on until 1992, before succumbing to the Mujahideen. Ironically, after their victory, the various groups of the Mujahideen began their internal struggle for supremacy, leading Afghanistan to a state of perpetual civil wars.

War, what is it good for?

The Soviet miscalculation

The reasons for the Soviet debacle in Afghanistan are many and varied. Most scholars tend to focus on military fallacies and mistakes. Among the most notables was that the Red Army was trained for more conventional warfare and wasn’t ready to deal with the Mujahideen guerilla tactics. Furthermore, its intelligence was imprecise, rendering its actions often ineffective. An additional problem was that their allies proved mostly worthless, while their enemy was too adaptable to be beaten. This stemmed from the Kremlin’s complete misunderstanding of Afghan mentality and tradition, ignoring a fact that war for national liberation would garnish much wider support than one against an oppressive regime.

This brings up a political issue behind the Soviet failure. The military officials were aware that a victory could be achieved with sufficient troops, which was according to some estimates around 400,000 men. However, the political leadership refused to send more troops, both because of the costs as well as internal and foreign politics. Instead, they simply told the army to try harder. This only eroded morale of the Red Army, but also led to an increase of violence against the civilian supporters of the Mujahideen. In turn, these only steeled the resolve of the Afghans to fight them.

However, faulty Soviet civil-military relations and miscalculations are only part of the equation. Cold War diplomacy was also a considerable variable. The USSR had to safeguard its prestige and reputation, often at the cost of sound military decisions. All the while, it was faced with constant diplomatic pressure from the majority of the world. Furthermore, the US, China, and numerous other nations continuously backed the Mujahideen. However, while this military aid certainly made Soviet enemies stronger, its role is often exaggerated. Most scholars agree that the US overplayed its importance for its own propaganda purposes. Nevertheless, constraints of the Cold War diplomacy limited Soviet maneuvering space and made a tough war even tougher.

Achieved nothing, lost everything

Despite all that, if the withdrawal from Afghanistan was merely a disgrace for the USSR, it would be fully comparable with the US in Vietnam. Both superpowers faced similar military dysfunctionality, international and internal pressures, not to mention Cold War proxy war diplomacy. However, the Soviet debacle in Afghanistan didn’t stop there, its consequences were much dire. First of all, it was an expensive war, but the Soviet economy was slowly crumbling in the 80s. The Soviet-Afghan War put an additional unnecessary strain on it. Secondly, Soviet extraction from Afghanistan, combined with the withdrawal of its other troops outside the USSR signaled weakness to its allies and opponents. It contributed to public exhibitions of anti-Soviet sentiment across the eastern bloc, as there was less fear from reprisals. Likewise, the whole ordeal finally deconstructed the Soviet image of a just, socialist, and anti-imperialist nation. The USSR lost all of its international legitimacy and reputation.

The worst of all is that it had a similar effect within the Soviet Union. It added to the crumbling of people’s delusions about the nation and its communist regime. As Gorbachev’s reforms allowed for more freedom of speech, many began questioning why did Kremlin wage such a pointless and costly war, and why was it led so poorly. It became one of the points for the critique of the Communist Party, contributing to the loss of faith in its leadership and its supposed ideals. All the while, hundreds of thousands of disgruntled Soviet veterans added their voices to various anti-government organizations. In essence, the Soviet-Afghan War was one of the important factors that led to the collapse of the USSR. It undermined the already weakened Soviet economy and added to the loss of faith in Soviet ideals and unity. It is precisely for this reason that the Soviet debacle in Afghanistan can be seen as much worse than the American failure in Vietnam.

A Red Army veteran (though not likely from the Soviet-Afghan War) protesting in 1990 on the Moscow streets. from theguardian.com

Despite that, the Americans learned nothing both from their own and Soviet disasters. They repeated the same mistake, waging their own US war in Afghanistan, one that followed similar development as the Soviet invasion, lasting 20 years before it ended in summer 2021. What will be its effect on the United States is yet to be seen, as its faces its own internal and external turmoil.