Table of Contents

The 1990’s, a decade of changes. Not only the end of the 20th century was nearing its end but also the whole system that arose from World War Two. Europe, made of two blocks, was changing its clothes. It was entering the age when all of its nations strived to become one. Still, some of these nations were on their way to break down. One, however, did it for the sake of everyone involved. This is the story of probably the most civil breakup in history - the breakup of Czechoslovakia.

How Czechoslovakia was born

In 1918, another world was collapsing. The 19th century Europe built on pillars of great empires, was collapsing. One of those empires was the Austro-Hungarian Empire - a “Dungeon of the Nations”. On its ruins, after the First World War, free nations formed their own countries. These were the nations that centuries ago lost their freedom and the time came for them to resurrect. Some nations, however, didn’t restore in their previous orders. Instead, they formed new countries in union with other nations. Such was the case with Czechs and Slovaks. Two old European nations hadn’t gone their own paths, but joined in one state.

Already at the start of the war, the Czechs and Slovaks sensed the time was right to set themselves free. In 1916, Czech and Slovak emigres in Switzerland formed the Czechoslovak National Council, an official representative of both nations that set independence as their ultimate goal.

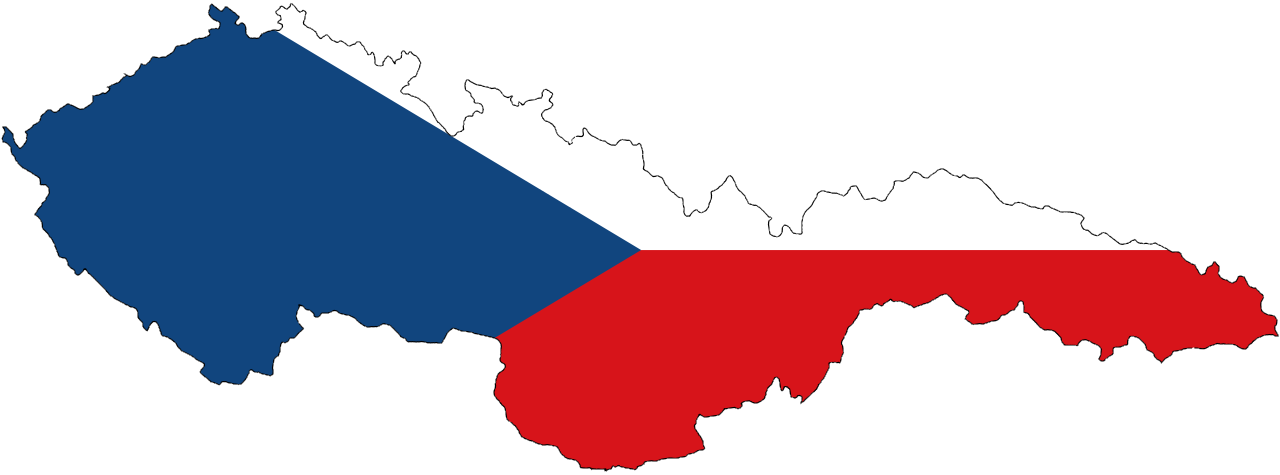

In Autumn 1918, the war was over and there was no obstacle for Czech and Slovaks to fulfill their dream. Earlier that year, on May 13, they signed the Pittsburgh Agreement to form a common country. Finally, on October 18, 1918, President Tomash Masaryk declared the independence of Czechoslovakia.

Flag of the Czechoslovak National Council (Public Domain)

One but Different

Why did the two nations decide to enter marriage in the first place and not go along separate national lines? What was the thing that brought them together? Both the Czechs and Slovaks had aggressive neighbors. Czechs were encircled and endangered by Germans, while Slovaks suffered oppression from Hungarians for a long time. To make the threat even bigger, both Germans and Hungarians had numerous national minorities in Czechia and Slovakia respectively. Only as a united nation, Czechoslovaks were able to resist their aggressive attitude.

The question was how united they could stand. Certainly, neither Czechs nor Slovaks could find a closer nation than each other. Still, the differences between them were large enough to become an asymmetric nation.

The biggest difference was the cultural one. By 1918 Czechs established themselves as a progressive society with highly developed civil, institutional and cultural attributes. Slovaks were still lagging behind in all these fields.

An especially important cultural difference was the language. There was an idea that Czech cultural supremacy might prevail in establishing a common language. During the 19th century, however, Slovak language and literature have already established foundations for independent development. There was no way that neither their culture, nor language could merge with the Czech.

Another obvious difference between the two nations was the economy. Czechs, being under the German economic influence, have developed their industry and economy to the level of the leading European countries. It was far above Slovaks, who still based their economy on agriculture. Unlike culturаl, the differences in economy were more susceptible to changes in order to establish the balance in the country. However, this was another field where Czechoslovaks failed to unite. It didn’t happen until the end of the 20th century.

Nation on the Crossroads

Differences between the two nations marked the first 20 years of the history of Czechoslovakia. Apart from differences mentioned, the question of the federal organization of the country prevented Czechs and Slovaks from establishing a harmonious union. When in late 1930’s the Nazi threat overshadowed the Czechs, Slovak nationalists felt no obligation to help their compatriots. The country collapsed as if it never existed. In 1938, Hitler annexed the Sudetenland and shortly after the rest of the Czechs. Slovaks used the opportunity to establish a country of their own. It was a German puppet state, but still their own.

Adolf Hitler at Prague Castle - licensed by CC BY-SA 4.0

The war and the “independence” offered Slovaks nothing better than what they previously had. They just realized that in given circumstances the union was by far the best solution for both them and Czechs. Thus, the idea of a common state was resurrected in 1944 resulting after the war with Czechoslovakia reconstituted.

The idea was to build a country on a new, more righteous basis, but the 1948 communist coup d’etat brought it all down. Once they grasped the authority in the country, Communists pushed aside all projects considering the special position of Slovakia within the country. Czechoslovakia became an even more centralized country than it was before World War Two. Moreover, it slid into an authoritarian communist regime.

In the post-war division of Europe, Czechoslovakia gave up on its independence as well. It became the de facto puppet state of the Soviet Union, especially after the 1968 intervention of the Warsaw Pact. Even though the 1969 Constitution divided the country into two semi-autonomous subjects, until its end Czechoslovakia remained a state under the centralized rule of the Communist Party.

Velvet Revolution

In November 1989, Communism in Czechoslovakia was at its end. A 41-year-long suppressive regime crumbled in less than two months. It all started on November 17, 1989 when a large group of students gathered on the streets of Prague to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the famous 1939 event when Nazis violently suppressed the students’ protest in Prague. It was more than just a commemoration as students also raised their voice for more political freedoms and economic reforms.

‘Velvet revolution’ in Prague 1989. licensed by CC BY-SA 4.0

The protest was suppressed by riot police, but only for the day. The desire for change was unstoppable. With each day the number of protestors was increasing. On November 20, 1989 half a million people were on the streets of Prague. It didn’t last long before the protest spread throughout the rest of the country. On November 27 the entire country stopped for two hours in a general strike. Three days later, the one-party system was officially abolished. On December 10, 1989, the first non-communist government was formed and on 29th of the same month, Vaclav Havel was elected the president of the country. Czechoslovakia entered the age of Democracy.

The Breakup of Czechoslovakia

Poor Marriage

With Communists, the oppressive and centralized government was gone as well. All the things pushed under the carpet were brought out to the light of the day. So was the question of Czech-Slovak relations within the joint country.

Even though the theme of the dispute remained the same, the differences between the two nations were not the same as they were. During the 50 years of communism, the Slovak economy grew almost to the same level as the Czech. Living standard of Slovaks increased and so did their awareness of political rights. On the other hand, Czechs believed that the Slovak growth was made at their expense and that things needed to be changed.

![Vladimír Mečiar (L) and Václav Klaus discuss the division of Czechoslovakia in 1992 - from [TASR archive] (https://www.tasr.sk)](vladimir-meciar-l-and-vaclav-klaus.jpeg)

Vladimír Mečiar (L) and Václav Klaus discuss the division of Czechoslovakia in 1992 - from [TASR archive] (https://www.tasr.sk)

Even though it seemed natural that in the democratic arrangement it would be easier to find a joint language to overcome the differences, the situation became even worse. Even after more than 70 years of life in one society, cultural prejudice was still present. For Czechs, Slovaks were an inferior younger brother who needed tutoring, while Slovaks accused Czechs of monopolizing all aspects of their lives.

More important were opposing views of both nations’ political leaders on the future of the country. The Czechs desired a more centralized state and the Slovaks were in favour of a loose federation. Czechs wanted to implement radical and free-market based economic reforms, while Slovaks opted for a much slower transition. It was like a marriage where both spouses wished for different things in their lives and accused each other for the poor situation they were in.

Velvet Divorce

It is important to note that the accent on things that separated Czechs from Slovaks was imposed not by a broad public, but by the leading political parties in Czechia and Slovakia. After the fall of communism, two parties emerged as leading organizations: the Czech Public Forum (Občanské fórum: OF) and Slovak Public Against Violence (Verejnosť proti násiliu: VPN). Both parties supported democratization of society, but diverged on the question of the constitution of the federation.

It didn’t last long for the first quarrel to occur on the matter. Whatmore, it was a rather bizarre conflict that remained known as the Hyphen War. The dispute arose when president Vaclav Havel proposed in early 1991 to change the official name of the country to Czechoslovak Republic by erasing the word “Socialist”. The proposal was strongly opposed by Slovak VPN, who proposed the name Federation of Czecho-Slovakia. This was a proposal that the Czechs found unacceptable because it was reminiscent of the Second Republic period prior to World War Two. Finally, a compromise was made and the country was named Czech and Slovak Federative Republic.

Somewhat at the same time, the political spectrum in the country crystalized. The OF split up into two parties: the conservative Civic Democratic Party (ODS), led by Vaclav Klaus and Civic Movement (OH). Slovak VPN also had a group that separated and formed a Movement for a Democratic Slovakia - HZDS, led by Vladimír Mečiar.

During 1991, several rounds of negotiations about the constitutional arrangement were held between Czech and Slovak representatives. The first such event was held in Kromeriž in June. It gave no results as neither side was willing to give in on the questions of the competences and the constitutional organization of the federation. The only thing they agreed to was that the people had the right to decide on the future of the country at the referendum. Another was the formulation of the referendum question, yet another obstacle on which both sides were unable to find an agreement.

The transition of the economy that started in 1991 was also a painful experience for the entire country. Slovakia especially suffered with an increasing unemployment rate. They, naturally, blamed the Czechs for the situation, especially the Minister of Finance Vaclav Klaus. Czech leaders certainly did nothing to lessen the antagonism of Slovak politicians toward them. Already in the beginning of 1991 they stopped with transfer payments from Czech budget to Slovakia. They behaved as if they already lived in separate countries.

The talks that continued in 1992 only showed that there was little chance of making any kind of a compromise. When, after the 1992 elections, ODS and HZDS established themselves as leading political organizations, the situation became even gloomier. With both parties standing firmly on different standpoints, it was difficult to believe that the joint country had a future. Paradoxically, both parties opted for the survival of Czechoslovakia in their election programs. even the broad public was in favor of the common state.

After the elections, a series of coalition negotiations were held. Neither of them resulted with agreement, except for the fourth, the last one. On June 19, 1992, Klaus and Mečiar finally agreed that the best solution was to separate. In July 1992, the Slovak National Council accepted the Declaration of Independence of the Slovak Nation. Later that month, President Vaclav Havel, strongly supporting the common state, resigned. For the last time in its history, the Czechoslovakian Federal Parliament assembled on November 25, 1992. By a very close call, it adopted a constitutional law on the dissolution of federations. The law was to be put into effect on December 31, 1992.

Slovaks celebrate New Year 1993 and the emergence of the independent Slovak Republic in Bratislava. (Source: TASR archive)

Final words

And so, 1993 New Year’s Eve was the last for Czechoslovaks. On January 1, they woke up in Slovak Republic and Czech Republic. The breakup was made in the most civilized manner with the national territory divided along the existing borders. Whatmore, it proved to be a refreshing start for both nations to establish good relations that they never had while living in the same country.

Further Reading

-

Wrobel, Adam. The Dissolution of Czechoslovakia, Historical analysis of the causes of the partition of Czechoslovakia. Malmo University, 2020

-

Wheaton, Bernard. The Velvet Revolution Czechoslovakia, 1988-1991. Taylor and Francis, 2018.

-

Shepherd, Robin H. E. Czechoslovakia: The Velvet Revolution and beyond. Palgrave, 2001.