Table of Contents

With the recent 35th anniversary of a disaster, popular series about it as well as recent signs of renewed heating up, Chernobyl once again came under the spotlight. Even without such recent trends, as the most serious nuclear disaster in human history, the Chernobyl meltdown is without a doubt a topic that has a long half-life. However, most research and stories revolve either upon what caused the catastrophe or the effects of its radiation on health and ecology. Yet, another interesting question that can be asked is if and how did the Chernobyl disaster contribute to the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Short story with never-ending consequences

Meltdown and immediate response

On April 26th, around 01:23 AM, a critical failure of Chernobyl’s reactor No. 4 led to a nuclear meltdown, followed by a raging fire and steam explosions. Ironically, the disaster struck during a scheduled safety test. The test was supposed to recreate conditions of a power outage, aimed at creating a procedure for maintaining cooling with water circulation until backup generators could restore the proper functionality of the reactor. Such tests have been carried out since 1982 when a possible safety hazard was noticed with the startup time of diesel generators which would leave the reactors without proper cooling for over a minute. The solution was to use residue power of the reactor’s turbine to power the pumps for at least 45 seconds, reducing the risks. However, even with installed modifications, none of the tests proved successful.

The test in 1986 was planned for April 25th, during the scheduled reactor shut down. However, minutes before the test began, the city of Kyiv asked for postponement as a failure of another power plant left the grid with an electricity shortage. Thus, the testing resumed later that evening, when the less prepared night shifts took over the plant. Around midnight, the test began. However, within thirty minutes the first issues arose. The reactor power declined sharply, a problem erroneously circumvented by removing control rods. Despite the ominous start, the test continued. By 1 AM, the reactor seemed somewhat stable, though still below the desired power level. The test preparations continued, beginning the experiment at 01:23 AM, adding additional stress to an already unstable reactor, starting a chain reaction that within less than 60 seconds led to at least 2 explosions, which scattered radioactive debris and started a fire both in the reactor as well as the rest of the plant.

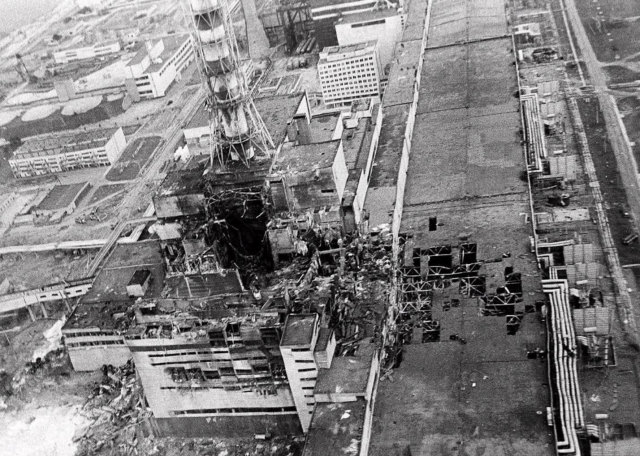

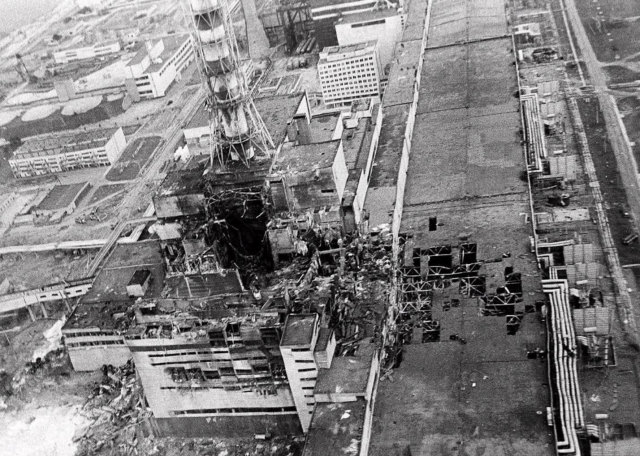

A photograph of a blown-up building that housed reactor No.4 in Chernobyl.

Within minutes, firefighters arrived at the scene, combating the fire which put other reactors in danger. At the same time, most of the plant staff continued to work on containment. Both groups were either unaware of an incredible amount of radiation or working despite it due to their sense of duty to protect others. By the early morning, around 6 AM, all the fires apart from the one in the core were put out, while other reactors were in process of shutting down. Nevertheless, the nuclear cat was now out of the bag.

Government response and shifting blame

By then, it should have been clear it was a major disaster that required a quick and organized response from the authorities. However, from the local party cadres, all the way up to the Kremlin, bureaucracy and inner politics bogged down the decision-making. Most notable was the fact that evacuation of Pripyat, a service town for the nuclear power plant, began only in the early afternoon of April 27th. Furthermore, the news about the incident was publicly announced in the evening of the following day, claiming it was only a minor accident. Earlier on 28th, Swedish nuclear power plant detected high levels of radiation over 1000km away from Chernobyl, asking the Soviets if anything happened on their territory. The Kremlin admitted that a limited nuclear accident did occur, but only after the Swedes threatened with a report to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Evacuation of Pripyat on April 27th, 1986. from history.com

All the while, tens of thousands of workers and soldiers continued to work on containment and cleanup, pouring liquid nitrogen, trying to cool down the reactor, filling the core with various materials to slow radioactive emission, pouring first layers of concrete, and cleaning the debris. Despite all that, the fire inside the core burned until May 10th, continuously releasing more and more radioactive particles into the air. In contrast with the severity of the disaster, the Soviet government reacted rather lukewarmly. The May parade in Kyiv was held as planned, no warnings or detailed accounts were published. It was only on May 6th that the officials in Ukraine closed down schools, advising people to stay indoors as much as possible and avoid eating leafy vegetables. In the upcoming days, the truth started to come out, crowned with Gorbachev’s first public announcement on May 14th, claiming the worst had passed.

In the following weeks and months, the Soviet government continued to work on cleanup of radioactive debris, construction of the famous concrete sarcophagus, and resettling hundreds of villages both in Ukraine and Belorussia. By then, most of the world was aware of the severity of the disaster, as radioactive clouds reached western Europe as well. Thus, an IAEA conference was held in late August, where the brunt of the blame fell on power plant operators, largely disregarding design flaws of the reactor, bureaucratic mishandling of the plant and other contributing factors. Thus, by early 1987, it seemed that for the Kremlin, the worst had really passed.

The “fallout” of the Chernobyl

Soviets in front of the world

The Chernobyl disaster put a lot of international pressure on Moscow, as the radioactive fallout spread across Europe in the weeks following the accident. Even worse, the initial denial made them even more suspicious to the westerners, who were quick to exploit the opportunity in the Cold War rhetoric. US President Ronald Regan immediately used the opportunity to emphasize the evilness of the Soviet regime as it refused to communicate openly with both the world but also the Soviet citizens. In essence, he pressured Gorbachev to position the Kremlin more in line with his proclaimed “Glasnost” policy of increased openness and honesty of the Communist Party.

Meeting between Ronald Regan and Mikhail Gorbachev in late 1986. thenation.com

At the same time, the disaster publicly exposed the cracks in the Soviet system for the first time. Before the accident, the US was aware that the Soviet Union faced economic difficulties, but there was little doubt about the stability of the regime. Yet, after Chernobyl, it was clear to many observers that there were many potential holes in the USSR, something Regan as a devout anti-communist was more than eager to exploit. A nuclear disaster was a fine point to convince Soviet allies and puppet states that the Kremlin wasn’t able to take care of them if something like Chernobyl happened on their own soil. At the same time, Regan’s administration realized that their plan to outspend the Soviet Union was a valid strategy to bring down “the evil empire”. Thus, in a way Chernobyl showcased an exposed wound for the west to exploit, attributing to the foreign pressure that played a part in the dissolution of the USSR.

Economic impact

While the Chernobyl accident did rattle some alarms in the west, for the Soviet government harsh words probably hurt much less than the expenses. While the nation was already in financial difficulties, a disaster of such scale only added additional expenditures. Over the next several years after the accident, the Kremlin spent around 18 billion rubles on various disaster-related alleviation, from the containment structures and lost vehicles to fallout cleanup to the relocation of thousands of peoples in Belarus and Ukraine. According to Gorbachev, it was exactly those expenses that tipped over the USSR leading to its dissolution, more than any other factor. However, such claims seem far-fetched. If Moscow’s accounts were as hard-hit by the cost of mitigating the effects of Chernobyl, where did the Kremlin find 21 billion rubles for its 1988 military budget? Furthermore, according to CIA estimates, the Afghan War (1979-1989) had a similar cost to the reported Chernobyl-related expenditures.

Thus, Gorbachev’s claims may be closer to his attempts to redeem himself politically than reality. A further addition to this conjecture is that the area around Chernobyl wasn’t agriculturally worthy, meaning that a long-lasting economic effect wasn’t as bad. Furthermore, in a relatively similar period USSR suffered severe droughts and a destructive earthquake in the Caucasus, thus blaming Chernobyl for bankruptcy of the union seems less and less viable. Moscow’s economy was in a long decline before the disaster happened, as evidenced by Gorbachev’s speech in 1985. However, clearly the disaster created an additional strain on the already fractured Soviet Union.

Eradicating the communist system

The bankruptcy of the system

Despite encumbering the USSR economy and its international prestige, the Chernobyl accident did create a much significant ripple in the fall of the Soviet Union. When Gorbachev ascended to the top of the party and the union in 1985, he promised a more transparent government more open to public discussions. The Glasnost reforms began to materialize by early 1986, just around the time of the disaster. Yet, despite the promises, the initial reaction of the party cadres was silence and denial, as it was the modus operandi of previous times. Then in a matter of days, Soviet people began learning more and more, as loosened censorship began leaking information to the public. Of course, this was partially caused by the fact that the effects of the meltdown were too big to sweep under the rug, yet it seems clear that it was helped by Gorbachev policies. Regardless of underlying reasons, the Soviet public became vary of the effects of the disasters. Even worse for the Kremlin, the people also lost a significant level of trust in their government.

The most shocking realization was most likely the fact that at certain points it seemed that the government cared more about preserving its image and ideology than the security of its citizens. From some, it posed the question whether they could trust the government when they said that food was safe for eating, air for breathing, water for drinking, etc. Suspicion was born, at least partially. For others, the trust was lost in the entire system and mechanism of the government, further exposing political and economic corruption on various levels of the party. People were getting tired of the excess of bureaucracy running their nation. Among the Ukrainians, a feeling of once again being sacrificed for the Russians in Moscow also steered up nationalistic feelings. There were also other layers of rising public dissatisfaction caused by the realization about what happened in Chernobyl. Yet all of them together began forcing the further expansion of Glasnost’s ideal, asking for more openness. Thus, the meltdown in Chernobyl resonated and dispersed the reformist ideas in the Soviet public, pushing Gorbachev’s policies much further than he even likely planned.

People got sick

It seemed that after the Chernobyl disaster, the Communist Party faced a challenge on top of the challenge, both internally and externally. All the while, thousands of Soviet citizens across Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia began feeling the consequences of the disaster. There were various health effects caused by exposure to the radiation, and people were getting ill and dying. At the same time, no matter how limited the effect on Soviet agriculture on the whole, certain areas did suffer from ecological destruction caused by the accident. All the while, the government continued to claim the worst had passed, that everything was fine. In the end, people got sick with such treatment. They had enough. Some simply lost faith in the party and communism as an ideology, while some even began exploring the possibilities to change the system.

ERecent photo of an abandoned building in Pripyat still adorned with rundown symbols of the USSR. from history.com

Final words

In a more global assessment of the dissolution of the USSR, it seems that it was exactly this loss of faith and trust that caused the final fall of the communist giant. With that in mind, it is clear that the disaster of Chernobyl did play a role in exposing all the faults and cracks in the Soviet system, maybe even dispersing the last thread of loyalty and hope among some of the people. However, claiming it was the main force behind the fall of the Soviet Union seems a bit excessive. It was just one of the nails in the coffin, certainly speeding things up. Yet, even before the Chernobyl accident, it was clear that if the system didn’t change, the union would disintegrate.