Table of Contents

Can you name a war fought by Icelanders? Kind of a difficult task. One would have to search deep in the past to find when was the last time inhabitants of this remote northern island resorted to weapons and methods of warfare. Well, nothing strange for a country that doesn’t even have a proper army and hasn’t had one for centuries. Yet, in the second half of the twentieth century, in the midst of the Cold War, Iceland was involved in three related conflicts. Truth be told, the wars fought over fishing rights lacked usual military engagements. Still, they caused a severe crisis in international affairs, especially regarding the unity of the NATO pact. How come? Island fought the Cod Wars against one of its closest allies, the United Kingdom.

Fishing for life

In the years when the communist threat occupied the heads of western countries’ leaders, it seemed impossible that a thing such as fishing rights might jeopardize the stability of the NATO pact. For Icelanders, however, it was a matter of life and death.

Before it became a posh tourist destination and banking heaven in the late twentieth century, Iceland’s economy depended almost entirely on fishing. For a long time, Icelanders enjoyed the wealth of the island waters, swarming with various fish species of which cod was the most important. However, in the late 19th century, the wealth of the Iceland waters attracted fishers from other countries, primarily the United Kingdom. The turmoil caused by World War One and World War Two got the most attention of the European countries, leaving the fishing in Iceland waters to the domestic fishers. Despite the shipping casualties because of maritime warfare, Iceland fishers enjoyed the benefits of the circumstances. They exported most of the fish they caught to the United Kingdom, bringing much-needed income to one of the poorest countries in Europe.

The end of World War Two turned the situation upside down. As European countries recovered from the war, the number of foreign trawlers fishing in Iceland waters increased. Overfishing that occurred, as a result, was a direct hit on Iceland’s economy. The government set the protection of the fishing grounds around the island as its priority.

Iceland – Siglufirði Siglufjörður By Hansueli Krapf

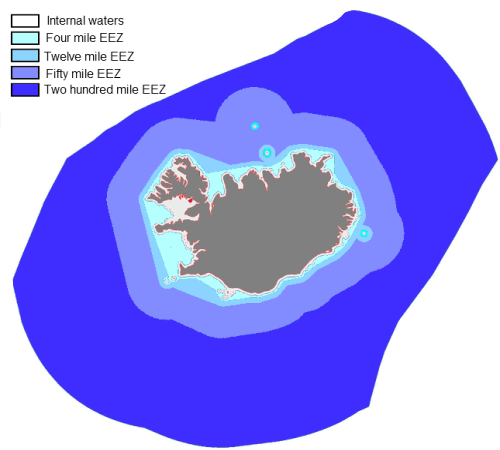

The first act in that direction was to increase the limit of Iceland’s Exclusive Economic Zone to 4 nautical miles. This act meant that no one except Iceland fishers could fish within four nautical miles from Iceland’s coast. This unilateral decision was met with great disapproval by the British, whose fishery industry benefited largely from fishing in the area. Their response was quick and severe. They imposed a landing ban on fish imports from Iceland. With Britain being their primary market, the British countermeasures severely struck Icelanders. It was how it all began.

The conflict was looming, and the first to try to use the opportunity were the Soviets. They stepped in by offering Icelanders to buy their products, hoping the deal might result in attracting the country to their block. The United States, a military protector and a generous benefactor to Iceland’s economy, responded in the same manner and persuaded other countries to buy fish from Iceland. It was of great importance for the Americans not to allow Iceland to fall into the hands of the Soviets. Only for that reason, the dispute between Iceland and the United Kingdom was resolved in 1956. The British lifted a ban and agreed to a 4nmi exclusive zone. The quarrel was far from over, though.

The First Cod War

Two years after the two countries agreed to resolve the conflict, the Icelanders returned the dispute to a starting point. On September 1, 1958, Icelanders made a new extension of the Exclusive Economic Zone. This time they set the zone limit to 12 nautical miles. The British were furious with the new measure and decided not to follow it. This time, they had the support of all other NATO members, including the United States.

Icelanders had a calculation of their own. The number of British trawlers fishing around their island increased, threatening to significantly reduce the fish population, especially cod. They believed that extending the exclusive zone could put the fishery under control.

The British continued to send their trawlers to the disputed zone. This time, British fishers had the protection of the Royal Navy in case Icelanders decided to use the force. It was precisely what Icelanders did. Even though Icelandic Coast Guard was incomparable in size to the British Royal Navy, the second largest in the world, it certainly didn’t lack courage.

It was during the First Cod War that vessels of two countries confronted each other. Determined to defend their waters, Icelandic patrol boats engaged British trawlers and even fired blanks in attempts to force them to leave the waters. On several occasions, they collided with vessels of the Royal Navy, who rushed to help. It was only because of the size of their fleet that Icelanders couldn’t make a more significant stand in the conflict.

Fishermen on board a British trawler fishing off the coast of Iceland Mirrorpix/Getty Images

The lack of sea power Icelanders replaced with diplomatic actions. More precisely, it was blackmail they resorted to. Iceland was a NATO member and had a Defence Agreement signed with the United States that allowed the U.S. Armed Forces to station their troops on the island. Iceland was a precious ally, as it provided NATO bases to hold the northern Atlantic under control. Aware of their position, the Icelandic Government threatened to leave NATO and break the Agreement with the United States unless the British agreed to make a satisfactory conclusion to the dispute.

With the Soviets waiting behind the bush to jump in and replace the Americans on the island, NATO officials rolled up their sleeves to find a solution that would satisfy both sides. It was evident that the Icelanders had an ace up their sleeve and that it would make the final settlement in their favor. It was precisely what happened. In February 1961, two nations agreed. Iceland was granted a 12nmi exclusive zone, but on condition to allow the British fishing rights in the outer 6nmi zone in certain seasons for three years. The Icelanders won the First Cod War.

The Second Cod War

The fishing rights dispute fell into a lull for an entire decade. Both sides stuck to their fishing zones during that period, but fishing intensity increased. The overfishing resulted in a sudden and catastrophic decrease in the herring population. In just one decade, the number of herrings declined from 8,5 million tons to almost nothing. It was a massive blow for Iceland’s fishery, which was about to worsen. If nothing was done, the same would have happened to cod by the 1980s. In the past, Iceland authorities tried to start the dialogue in the United Nations on fishing regulations, but with no result. The conclusion was they had to act unilaterally once again.

On September 1, 1972, the Government in Reykjavik enforced a new law that set the boundaries of the Exclusive Economic Zone to 50 nautical miles. Needless to say that the law provoked the British, who declared that, like 14 years ago, they had no intentions of obeying the law. Even the Warsaw Pact members supported the British in the dispute this time. The big powers feared that the decision might set a precedent for other extensions.

The next day, Iceland patrol ship ICGV Ægir chased away 16 British trawlers out of the newly set exclusive zone. Instead of direct engagement, Iceland Coast Guard resorted to new tactics. They started to use net cutters to cut the trawling lines of foreign vessels trespassing the exclusive zone. It was a simple but effective weapon. The patrol boat dragging the net cutters would simply pass behind the trawler. At some point, the net cutters would hook up onto the trawler’s line and cut it, thus releasing the net.

Klippur, the net cutters

The first “net cutting” took place On September 5, when ICGV Ægir engaged British trawler Peter Scott. British sailors, angry at losing their net, threw everything they had at Ægir, cursing them along the way. The tactics proved to be so effective that the British formed a special naval group to follow and defend the trawlers.

From May 1973, British trawlers were escorted to disputed waters by Royal Navy frigates. In the air, a patrol Hawker Siddeley Nimrod aircraft reported the whereabouts of Icelandic patrol vessels. It was a proper countermeasure that reduced the effectiveness of the Iceland Coast Guard patrol vessels.

Lock gate of the northern Atlantic

The actions taken by the British enraged the Icelanders, who vehemently protested. They even tried to appeal to the United States to act in accordance with Article 5 of the NATO pact and the Defence Agreement and protect their territory by attacking the British fleet. The rage caused by the British presence also resulted in massive protests in front of the British Embassy in Iceland’s capital. The situation went from bad to worse when a collision of ICGV Ægir with a British frigate resulted in the accidental death of an Icelandic engineer, the only casualty of the war.

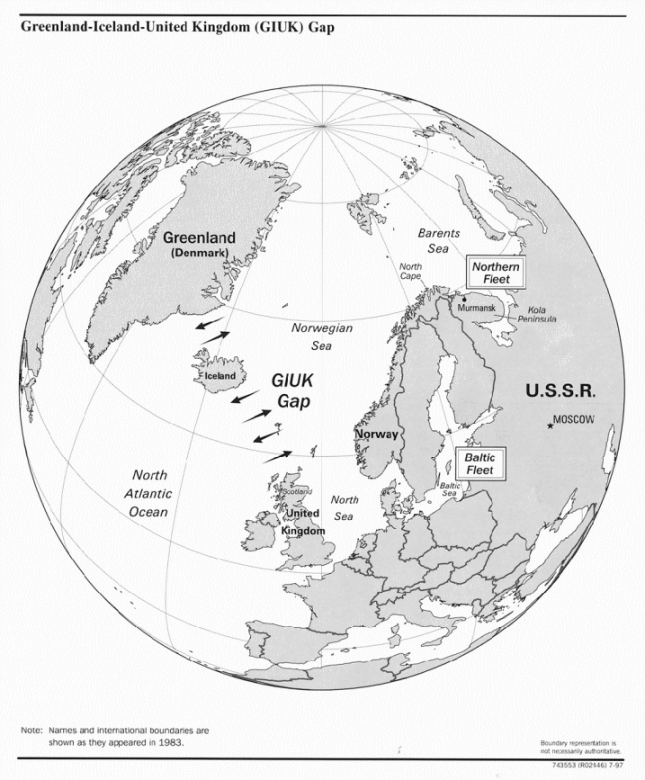

The Icelanders had no choice but to resort to a proven method of blackmailing once again. Indeed, this time Icelanders were serious about leaving the Pact as the events showed it provided them with no protection. A red alert was called in the NATO Headquarters. Iceland leaving the Pact would seriously undermine Western democracies’ collective defense system. Without access to Iceland ports, NATO would hardly hold the notorious Greenland-Iceland-UK gap under control. The GIUK Gap is a water passage between the UK, Iceland, and Greenland leading from the Norwegian Sea into the Atlantic Ocean. More importantly, it was the only passage for Soviet submarines arriving from the Kola Peninsula. Blocking and surveilling the gap was the core of NATO’s naval strategy.

Klippur, the net cutters

For this reason only, the Secretary-General of NATO arrived in Reykjavik to persuade the Iceland Government to ease the tensions and reach a solution with the British to end the dispute. The British did their part of the job by recalling the fleet from Iceland’s waters.

The agreement was signed on November 8, 1973. The Icelanders won another war. They were granted the exclusive zone of 50 nautical miles in return for allowing the British an annual catch of 117,000 tons of fish. The Agreement was valid for two years.

Third Cod War

The peace between the two nations lasted only as long as the Agreement was in power. To no one’s surprise, only days after the Agreement expired in November 1975, Iceland and the United Kingdom started the Third Cod War.

Earlier that year, Iceland expanded the Exclusive Economic Zone to 200 nautical miles to establish complete control over fishing rights and prevent overfishing. Like on previous occasions, the British did not recognize the increase of the exclusive zone and continued fishing. Learning from previous experiences, the British sent a substantial fleet of frigates to defend their trawlers. This time, they showed a more serious response to the Icelanders, who also sharpened their weapons for the conflict.

The event on December 11, 1975, showed that the Third Cod War was about to evolve into the most serious conflict in the dispute that lasted for 25 years. That day Icelandic patrol boat “Thor” engaged three British ships that entered Iceland’s territorial water. Eventually, two of the British vessels, a large tug “Lloydsman” and a supply vessel “Star Aquarius,” hit the “Thor” and caused severe damage. Much smaller than the British counterparts, “Thor” responded by firing a blank round and shooting the bow of the “Star Aquarius” with a live round. “Thor” was engaged in another conflict in January 1976 that ended with a hole in its hull. On the other side, the British frigate HMS Andromeda suffered a slight dent in the hull.

In both incidents, each side accused the other of initiating the collision. Iceland even appealed to the UN Security Council to resolve the incidents, but with no result. The conflict went so far that on February 19, 1976, Iceland broke diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom.

The clashes on the sea continued. During the six months that the war lasted, the number of collisions reached thirty-five. Neither side was willing to stand down, and the conflict deepened. Eager to defend its economic independence, Iceland tried to acquire missile-armed gunboats from the United States. The US administration rejected the offer as they didn’t want the conflict to escalate further. How serious Icelanders were in their intentions says the fact that they turned their attention to the Soviets, who offered their Mirka-class frigates instead.

The EEZ of Iceland at each stage

Once again, the Icelanders threatened to leave NATO. This time, they were really close to making such a decision as the Iceland leftist government threatened to close the airbase in Keflavik. The airbase used exclusively by the US Air Force was vital in controlling the GIUK Gap. The Americans simply couldn’t allow the base to close, so once again NATO stepped in to resolve the conflict.

The final agreement, one that ended the Code Wars for good, was signed on June 1, 1976. Iceland was granted a 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone, and the British were allowed to keep 24 trawlers within it, with the maximum annual catch of only 30,000 tons of fish.

Like the previous two, Icelanders won the Third Cod War. The dispute over fishing rights ended once and for all. The diplomatic relations between the two nations were restored and have constantly improved ever since.

Icelanders fought for their economic independence and have won. On the other side, the British defended not only their economic interests but their pride as the second-largest naval power in the world. It was only because of the higher cause that they gave in to Icelandic demands. Losing rights to fish in waters near Iceland resulted in the collapse of the fishing industry in northern England and losing thousands of jobs. What about cod? The overfishing never ended, though. In 1998, the World Wildlife Foundation placed cod on the endangered species list, making it the only true casualty of the Cod Wars.

Sources

Further reading

- Bird, J. A. “Cod War Weather.” Weather 32, no. 7 (1977): 271-74. doi:10.1002/j.1477-8696.1977.tb04571.x.

- Gudmundsson, Thorir. “Cod War on the High Seas.” Nordic Journal of International Law 64, no. 4 (1995): 557-73. doi:10.1163/157181095x00850.

- Guðmundsson, Guðmundur J. “The Cod And The Cold War.” Scandinavian Journal of History 31, no. 2 (2006): 97-118. doi:10.1080/03468750600604184.

- Jóhannesson, Gudni Thorlacius. “How ‘cod War’ Came: The Origins of the Anglo-Icelandic Fisheries Dispute, 1958–61*.” Historical Research 77, no. 198 (2004): 543-74. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2004.00222.x.

- Kurlansky, Mark. Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World. Vintage, 1999. fishers

- Mitchell, Bruce. “Politics, Fish, and International Resource Management: The British-Icelandic Cod War.” Geographical Review 66, no. 2 (1976): 127. doi:10.2307/213576.

- Sverrir Steinsson, “Why Did the Cod Wars Occur and Why Did Iceland Win Them? A Test of Four Theories,” MA thesis, School of Social Sciences, 2015.