Table of Contents

Introduction

The history of Libya has been a long walk from one invader to another. For two and a half millennia, indigenous Berber tribes have seen many foreign invaders ruling this part of North Africa. From Carthaginians and Romans to Vandal tribes who arrived after the Western Roman Empire collapsed. In the second half of the 7th century, an Arab invasion swallowed Libya with the rest of North Africa. The arrival of Arab invaders changed the image of the region for good, establishing the domination of Islam and Arab ethnic population for good. In the 16th century the whole of Libya fell under the rule of the rising Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans undisputedly ruled the region until the early 20th century. After the 1911 to 1912 Italo-Turkish war, the Ottoman rule was replaced with the Italian. So, when exactly did Libya become an independent state?

The defeat of Italy and its expansionist politics in World War Two opened the door to Libya’s independence. However, Libyans needed to deal with the interests of the victorious powers of World War Two to reach their goal. In the course of events that followed, there were moments when it seemed that everything would stay the same. Only the foreign rulers would change.

Libyan Arab Force Cap Badge

Libya in World War Two

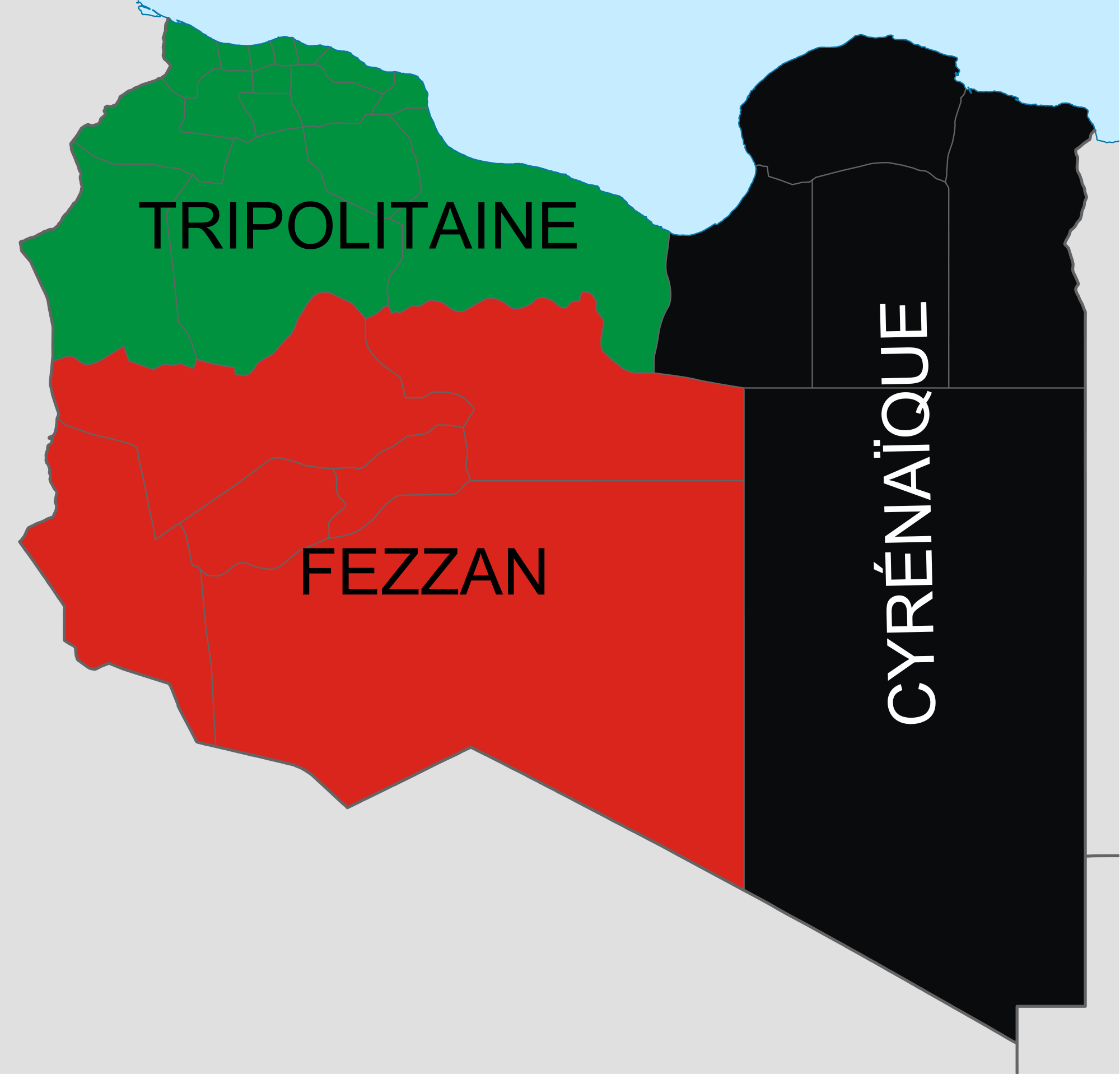

During their reign over Libya, Italians practiced an indirect governing system that allowed local tribal chiefs limited autonomy. The Italian Libya was divided into three traditional regions: Cyrenaica in the East, Tripolitania in the West and Fezzan in the South. Each region had its own traditional background and as such they were hardly making a unique Libyan nation.

When Italy entered the war in 1940, the regions differed in their standpoints on how to deal with the situation. Distant Fezzan seemed far from the center of the North African Campaign operations. In Tripolitania, the most inhabited region by Italians, people were reluctant to make any hasty action. They rightfully feared the Italian reprisals in case of uprising. They secretly did support Cyrenaicans who, close to the British in Egypt, were the only ones willing to fight. The way they saw it, freedom had to be earned, not given.

During the war, under the guidance of the head of the Senusi religious order Sayyid Muhammad Idris al-Mahdi al-Sanusi, Cyrenaicans organized the Libyan Arab Force. Consisting of five battalions, it was a small guerilla army that served as an auxiliary force to British troops during the North African campaign. Their contribution to the final victory was not huge, but it was enough to gain Allied sympathies. In March 1943, the British pushed the Italians from the entire Libya. French entered the country from the south and seized Fezzan. Two months later, the war in Africa was over.

The Aircraft Carrier of the Mediterranean

With the Italians gone, Libyan provinces were put under the military administration of British and French. Obviously, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica with many coastal towns were under British control. In the south, French troops entered Fezzan, the province’s neighbor to their colonies in Chad.

Libyan leaders were somewhat disappointed to learn that their freedom was still far from fulfillment, even though Italians were gone. In the words of British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, Libya would be given its freedom, but at the appropriate time.

The position of Libya in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea gave it an enormous strategic importance. Military leaders regarded Cyrenaica as the “largest aircraft carrier” in the Mediterranean. Any power that would establish air bases along the coast would have the entire basin under control.

Libya was too precious a possession for Britain to let go free. The decision on Libya’s future was therefore to be postponed for the period after the war.

The British doubted the competence of the future government to run Libya in a way they considered proper. Both Cyrenaicans and Tripolitans objected. British statements made them unsure if their independence was guaranteed. They feared that great powers had different plans for Libya, especially regarding the unity of Libya’s three provinces.

The ‘Big Three’ during the Tehran Conference to discuss the European Theatre in 1943.

In the Hands of the Great Powers

With high stakes on the table, it was clear that the future of Libya would be decided by the great powers. The principle of self-determination proclaimed by the Atlantic Charter in 1941 was put on hold in the case of Libya.

The first draft of what was supposed to be the future of Libya was made in summer 1943 by the United States Department of State. Unlike the British, Americans had little interest in the region. They made four different proposals for a solution to the Libyan question.

The proposals went from creating an international trusteeship of Great Britain, France and Egypt to a division of Libya. In this case Cyrenaica was going to Egypt and Tripolitania to Tunisia. The alternatives were to restore Italian rule in Libya and even to establish a small Jewish state in Cyrenaica. With these proposals on the table, Britain opted for the division of Libya.

Their idea was to establish Cyrenaica as an autonomous principal under Egyptian suzerainty. The Tripolitania would be returned to Italians, with the obligatory demilitarization of the province. What the British insisted on was the right to use the airfields they already occupied both in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania.

With all major powers in favor of this, or slightly modified, concept, it seemed that the idea of independence was unattainable for Libyans.

Red Threat

The Libyan question changed its course when the Soviets brought up their claims for trusteeship over Tripolitania. Claiming that the Americans and British had more than enough bases around the world the Soviets believed that, by allowing them to establish their own bases in Tripolitania, a balance of power would be achieved in the region.

With the Soviets in the game, the United States decided to take a more serious engagement in the Libyan question. U.S. Secretary of State John Byrnes offered a new plan for Libya to be put under UN trusteeship for a period of 10 years. After the transitional period was over, the country would have been granted independence. Byrnes secured British consent for his ideas, but the Soviets insisted on their claims. They made it clear during the Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers in December 1945.

In the years to follow, the Libyan question was dictated solely by the interests of the great powers. None of these hesitated to alter their previous standpoints if they didn’t coincide with current plans and interests.

On February 10, 1947, the Italian Peace Treaty was signed. Italy was obliged to renounce all rights to its former territories in Africa, including Libyan provinces. According to articles of the treaty, British and French military administrations would continue to govern these territories. Their future would be determined by the joint decision of leading powers: The United States, Soviet Union, Great Britain and France. The deadline for the agreement was one year starting September 15, 1947. After that, the issue would be submitted to the General Assembly of the United Nations.

Map of the three Governorates of Libya.

Libya Awakens

Meanwhile, Sayyid Idris arrived in Cyrenaica in November 1947 after a long exile. Before his arrival, he had already made claims to Britain to recognize the independent Sanusi Amirate in Cyrenaica under his rule. On the internal plan, Sayyid Idris secured his position by dissolving all political parties and forming the National Congress to support his rule.

In Tripolitania, political life sparked up after the province was liberated. A number of political parties were formed, all asserting the independence and union of all three provinces. The concession they were willing to make was to accept the rule of future king Idris.

In Fezzan, claims of local leaders for more autonomy were opposed by the French military administration. Contrary to international agreements, the French still intended to turn Fezzan into yet another of their African colonies. The French oppression caused the locals to organize into secret organizations.

Political claims for independence were louder with each day in Libya. However, the great powers were reluctant to make any concessions on account of their own interests.

The Commission of Investigation arrived in Libya in 1948 to assess the country’s readiness to take the path of independence. Representatives of all three Libyan provinces made their demands for unification and independence loud and clear. Acknowledging their sincere wishes, the Commission still reported that the country had no political or economic resources to support independence.

In the last session of the Council of Foreign Ministers, just two days before the deadline, a decision was made that the responsibility for solving the Libyan question should be transferred to the United Nations. By that time, the cards had switched hands completely. The Soviets have now advocated UN trusteeship over the entire unified Libya. Opposing them British, Americans and French who now found the concept obsolete and opted for the division of the country.

The First Country Created by the UN

In the public debates organized by the UN Assembly, there was still a question of Libyan readiness to become independent. There was also interest for the great powers to be considered.

At the time, the United States and Great Britain were engaged in turning the Wheelus Field into a strategic air base. For this reason, they opted against the UN trusteeship that would hinder their plans. They supported the Bevin-Sforza plan, which entrusted Libya to trusteeship of Italy, Great Britain and France. The plan was strongly opposed by the Soviet Union and Arab countries, who all asked for immediate independence, withdrawal of foreign troops and liquidation of military bases. The Bevin-Sforza plan was defeated in a UN Assembly vote.

In the light of new events, it became obvious that there was no other solution but to grant Libya an independence. Finally, on November 21, 1949, by the margin of a single vote, the General Assembly of the UN decided that Libya would become an independent state. The country would include all three provinces. A ten-member advisory council was appointed by the UN to help the Libyans draw up the constitution.

On 7th of October 1951, the National Assembly consisting of twenty members each from three provinces, approved the constitution of Libya.

On December 24, the King of Libya Sayyid Muhammad Idris al-Mahdi al-Sanusi, in a speech on a radio, proclaimed the United Kingdom of Libya - a federal, hereditary monarchy. The. Both Tripoli and Benghazi were named joint capitals. Libya became the first African country to free itself from European colonial rule and the first country to be created by the UN. More importantly, independent Libya spurred Arab nationalism in the region. It was the beginning of the end of colonial Africa.

Further reading

-

Vandewalle, Dirk J. History of Modern Libya. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

-

Bruce, St John Ronald. Libya: From Colony to Revolution. Oneworld, 2012.