Table of Contents

History has taught us that anything can happen. Literally anything. The number of events from our past that one would find hard to believe is endless. A unit saved by a pigeon. A submarine that sunk itself with its own torpedo. How about fighting a battle with no enemy on the other side? It happened to soldiers of the United States and Canadian armed forces on the small island of Kiska. Whatmore, during the World War Two battle known as Operation Cottage they suffered casualties of more than 300 soldiers. Their enemies, the Japanese, had no casualties. Of course they didn’t! They never fought in the battle.

World War Two Arrives to the States

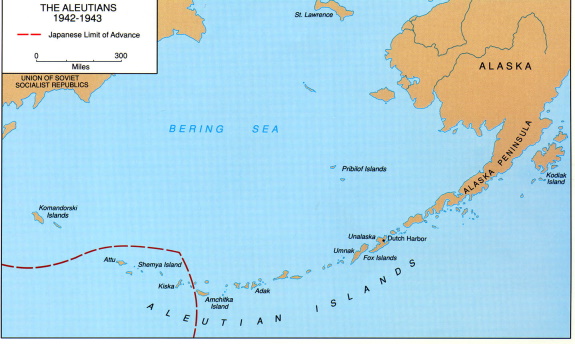

If you tried to search for the island of Attu, you would have to go to the northernmost corner of the Pacific - the Aleutian Islands. An archipelago of 14 large plus 55 small islands became a territory of the United States of America in 1867 when Alaska was purchased from the Russian Empire. Since then, it has hardly been anything more than a base for seal-hunting boats. How come then that one of the islands of the archipelago came into the center of this, more than awkward, event. It all began with the Japanese occupation of the islands of Kiska and Attu in 1942. This was the only part of the United States to be occupied during the war.

On June 3, 1942, the Japanese launched an attack on the Aleutians. The key target was Adak Island in the middle of archipelago, a task that Japanese failed to complete because of the strong resistance by the Americans Ultimately, after waging their options, Japanese command ordered their troops to land at islands of Attu and Kiska. With virtually no resistance, the Japanese seized the islands and began building their garrisons. By the spring of next year, Attu had 2,500 men garrisoned, while Kiska had around 6,000. On both islands, the Japanese built a formidable defense system inland of the island.

Aleutian Archipelago

A National Disgrace

Holding two islands in the remote part of the Pacific was not much of an advantage for Japanese in future war operations. The main operations of the Pacific Theatre took place thousands of miles away. For Americans, this was not much of a strategic issue, but more a matter of national pride. Or of disgrace, as some saw it. Attu and Kiska were the first pieces of American soil to be conquered by foreign troops since 1812 and the war with the British. The war would have probably ended with the Japanese on those islands, but the public pressure was enormous to retrieve them into American hands. If America was to lead the free world to victory, not even an inch of its soil should be left to the enemy.

Life in Attu and Kiska was not much of an idyllic one for the Japanese. The climate on Aleutian Islands was inhospitable with low temperatures, strong winds, cold rain and an average of 100 days in complete darkness. The good thing for the soldiers garrisoned on the islands was that there was no shortage of supplies.

The supply chain, however, was soon cut by the US Navy and the islands were put under naval blockade. Only every now and then would a Japanese submarine slip through bringing food, fuel and ammunition for the garrisons. On March 26, 1943, a Japanese fleet tried to break the blockade commencing the Battle of Komandorski Islands. The entire effort was futile, though. Japanese garrisons at Attu and Kiska remained cut off.

Japanese army General Yasuyo Yamasaki and officers in Attu Island, 1942.

Operation Landcrab

Throughout the second half of 1942 the US Army was piling up forces in the Alaska Command Area. By January 1943, there were more than 90,000 soldiers ready to be deployed to Aleutians. The first goal was landing on Amchitka island, only 50 miles away from Kiska. From Amchitka, American planes were able to bomb Japanese garrisons on a daily basis. Of the two occupied islands, the US Army command decided to launch an offensive on a smaller one first. A little less than 2,500 Japanese soldiers in Attu were expecting the attack. Knowing that they were facing a much stronger enemy, they withdrew to pre-built fortifications in inland mountains. Unopposed, US Army troops landed on the shores of Attu on May 11th, 1943. It was just calm before the storm. In 19 days that the Battle of Attu lasted, the American soldiers got to know the true meaning of the Japanese soldiers’ Bushido code. Fighting to the last man.

For the commander of the Japanese 301st Independent Infantry Battalion Yasuyo Yamasaki, surrender was never an option. Not even on May 29, when he and his men, starved and exhausted, were cornered down. Instead of laying down arms, Yamasaki ordered the Banzai charge. The attack was a complete surprise. For Americans, this was the very first time to see anything like this. The Japanese made a breakthrough all the way to support troops in the rear, but were eventually all killed. A total of 2,351 Japanese soldiers gave their lives defending the Attu Island. Only 28 of them survived. Operation Landcrab was a blow for Americans as well - 3,829 casualties of which 549 were killed.

Judging by the experience of soldiers who fought on Attu, the battle was a true horror. Fighting on inhospitable terrain and cold weather against a fanatic enemy was far from what they expected.

Dead Japanese military personnel lie where they fell on Attu Island after a final banzai charge

Operation Cottage

In war, fear is the greatest enemy of every soldier. After the Attu, American soldiers could have hardly expected anything other than the same level of resistance on Kiska. Whatmore, the garrison on Kiska was more than twice as large as the one on Attu. With lumps in their throats, 39,000 soldiers of the American 7th Infantry Regiment and Canadian 13th Royal Infantry Brigade sailed off to Kiska. Assessments were made that the entire 30% of them would be killed in the battle. On August 15th 1943, the Americans commenced landing operations on the western coast of Kiska. A day later, the Canadians landed on the northwestern part of the island. All that time a covering fire was provided from air and sea. An entire fleet of 100 vessels participated in the operation. They were pouring shells on Japanese positions - 330 tons during the first day of landing only. The 11th Air Force did their part of the job as well with 424 tons of bombs dropped on Kiska since mid-July. It was more than enough to silence the Japanese coastal defence.

Indeed, not a single round was shot on landing troops. Luckily, as the poor forecast of tides has caused landing boats to strand into volcanic rocks and make a complete jam. If the Japanese had responded, American soldiers would have been sitting ducks.

Part of huge U.S. fleet at anchor in Adak Harbor in Aleutians) ready to move against Kiska (NARA/U.S. Army Air Forces/Horace Bristol

The Japanese showed absolutely no resistance. It didn’t chase the fear away, though. The Japanese were waiting for them up in the hills, it was the same as Attu, Americans believed. With the sound of the Japanese war cry on their minds and fear in their hearts, the soldiers slowly moved inland.

Disoriented by the dense fog, Americans saw enemies everywhere. Frozen and scared, they fired at the slightest sound. And they were fired upon! Twenty one soldiers were killed during the first day of the offensive. The awkward thing was that the Japanese were nowhere. There was only a friendly dog wandering around. Still, soldiers were reporting discoveries of hot rice meals in bunkers and even heard Japanese soldiers yelling.

On August 16, Canadians landed and moved inland. They, too, were scared and affected by horrible weather conditions on the island. Like their American comrades, Canadians also turned out to be trigger-happy. Already on their first day, they stumbled upon enemies. A shootout started that ended with 4 killed Canadians and 28 dead on the other side. Unfortunately for them, these were not Japanese but Americans. The anxiety and dense fog have caused the allies to open fire at each other, believing they were shooting at the Japanese.

In the following days, American and Canadian soldiers continued to sweep the island, but Japanese were nowhere to be found. However, the number of casualties was still increasing. There were more examples of friendly fire, but the majority of soldiers were victims of Japanese booby traps and mines. On August 18 only, 70 sailors died when destroyer Amner Read struck a mine when entering the harbor of Kiska.

Ghost of an Enemy

As the days passed, it became clear there were no Japanese on the island. Reports of their presence turned out to be just hearsay. On August 24, Kiska was declared secure. But, where on earth did the 6,000 japanese soldiers disappear? Despite every day patrolling in the sky over Kiska, US aircraft failed to notice that the Japanese had left the island. They were also under the impression of the Battle for Attu. Realizing there was no purpose to defend the island, the Japanese decided to leave it. On July 28, in just one day, under the cover of dense fog, Japanese cruisers, destroyers and transport ships picked up the entire garrison and took them to safety of Kuril Islands.

U.S. Army intelligence did report reduced activity on the island past that date, but the commander of the operation, Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, believed it was just a sham and that the Japanese were waiting in the mountains. The truth was that Allies were fighting on an empty island. During the operation, they lost 92 men with another 221 wounded. Undoubtedly, the American public was glad to retrieve part of American territory from the enemy,but Rear Admiral Kinkaid was still put under fire for losing so many men in fighting against no one.

In the end, Attu and Kiska turned out to be good lessons for later operations in the southern Pacific islands.

Sources/Further Reading

-

MacGarrigle, George L. Aleutian Islands. U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1992.

-

Rhonda Roy, “The Battle for Kiska,” Esprit de Corps Magazine 9, no. 4 (2002)

-

How The US Suffered 300 Casualties Storming An Empty Island In WWII

-

Operation Cottage: A Cautionary Tale of Assumption and Perceptual Bias