Table of Contents

Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgy K. Zhukov is often credited for being one of the best generals in history, in the rank of Napoleon or Alexander the Great. He played a seminal role in the Soviet and, in turn, allied victory over Nazi Germany during World War II. Yet once the war was won and peace arrived, interest in his life dissipates. This poses a question - what happened to Zhukov after WW2?

From hero to a disgrace

On top of the ladder

Georgy Zhukov came from a poor peasant family, joining the Red Army in late 1918. His background was proved to be perfect for advancing under the communist regime, allowing him to slowly gain ranks. He played a minor role in the modernization of the Soviet forces but remained overshadowed by his superiors. Then in 1937, Stalin ordered the Great Purge, cleansing the Red Army from anyone deemed unreliable or a threat to the regime. Many perished, but Zhukov survived though according to various testimonies, he was close to being purged as well. This finally created space for Zhukov to advance further and faster, with his victory at Khalkhin Gol against the Japanese in 1939 catapulting him into the limelight.

From there, he continued his rise, becoming chief of the general staff in early 1941. In August of the year, Germany invaded and Zhukov played an important role throughout the war, taking part in defense of Leningrad and Moscow, the battles of Stalingrad and Kursk, as well as many other operations. In January of 1943, Zhukov was promoted to the Marshal of the Soviet Union, the highest military rank in the state, while he also became a crucial member of STAVKA. His achievements in World War II were crowned by personally accepting the German surrender in Berlin in May 1945. Immediately afterward, Georgy was appointed the supreme military commander of the Soviet occupation zone in Germany, while also holding no less than 3 Hero of the Soviet Union medals among many other honors. Overall, Zhukov was widely popular both in the USSR as well as with the allies, General Eisenhower in particular. His carrier seemed prosperous and secure.

The signing the German Instrument of Surrender in 1945, Marshal Georgy Zhukov is standing in the middle

To the backwaters

Early post-war carriers followed the upward trajectory. In early 1946 he was elected in the Supermen Soviet, the parliament of the USSR, followed by his official appointment as commander-in-chief of the Soviet ground forces. Despite seeming like he was at the top of the world, Zhukov’s fortunes weren’t to last. He was recalled to Moscow in March to assume his new duties, all the while a storm was brewing beneath the friendly facade. Unbeknown to Zhukov, Stalin and his closest associates began preparing another purge in the army, arresting and demoting numerous generals who were deemed too powerful and popular. With his popularity in the army, among the Soviet people, and his close contact with the foreigners, Zhukov became an obvious target.

In June 1946 he was summoned to a military council presided by Stalin, along with Molotov, Beria, and Bulganin. The war hero faced serious charges of Bonapartism, inflating his merits and misappropriation of trophies. For the latter, he was most certainly guilty, as his house was filled with jewelry, paintings, and many other looted items. However, it’s highly unlikely he had done anything against the party or counter-revolutionary. Furthermore, while the political leadership of the USSR of the council panned Zhukov, most other generals stood up for him or at least refused to back the charges of the party leaders. Regardless of their support, Zhukov was stripped of his newly gained position and appointed as commander of the Odessa Military District. It was a position far below his status, far from Moscow, and of little significance. Marshal tried to weather the problems stoically but suffered a heart attack. By early 1948, he was further demoted by being relegated to serve as the Commander of the Ural Military District, a position comparable to political exile to Siberia.

Troubles with Stalin

Such a rapid fall from the graces immediately brings up the question - why was Zhukov disposed of? Many historians and scholars tend to attribute that to some kind of personal jealousy and threat Stalin might have felt. It is hard to estimate how much truth lies behind these claims, as there is no written evidence of such feeling. Yet, it is known that the two often had their disagreements and that Zhukov occasionally felt like Stalin wanted to take his credits for victories on the front. Despite that, marshal himself never felt there was any bad blood between him and Stalin. Zhukov mostly blamed his closest associates Beria and Bulganin for turning the dictator against him, especially after the military council. By his own words, Stalin even protected him from being arrested and suffering a worse fate.

Of course, it is unlikely that any of Stalin’s underlings worked without at least his approval. Yet, Bulganin could have influenced him. According to Zhukov’s memoirs, two of them did have serious altercations, and Bulganin did seem somewhat jealous. Marshal didn’t hide this opinion, voicing it directly to Bulganin in a conversation after Stalin’s death. He said that it was him who put Zhukov in harm’s way under Stalin. Similarly, Zhukov often harshly criticized Beria in later years, hinting at a rather possible personal feud between the two of them, especially as the marshal showed open disgust for him. However, he never blamed him as openly as Bulganin.

Joseph Stalin and Marshal Zhukov in 1941

It is only “business”

Nevertheless, Stalin must have played a crucial role in Zhukov’s fall. In a totalitarian USSR, nothing was done without blessings from “Uncle Joe”. If personal grievances weren’t Stalin’s primary motive, as Zhukov himself thought, then it had to be of professional nature. While Zhukov did partake in post-war looting, and he acknowledged that mistake, it was only a pretext, not the real cause. Thus, it is far more likely that the answer lies in Stalin’s dictatorship than in Zhukov’s military or political faults.

Marshal noted in his memoirs that even while the war was still raging, but when Soviet victory seemed certain, Stalin began sowing seeds of mutual distrust between his top commanders. It showed clear signs that he was afraid that generals were gathering too much power between themselves. Furthermore, after winning the war, Red Army as an institution gained a lot of prominence and respect from the population, threatening an ideological system where the communist party was the most powerful and important organization in the state. Crucial evidence to support such interpretation is the fact that many other top generals were also deposed after the war, though not en masse as during the Great Purge.

Therefore, while Stalin most likely wasn’t resentful with Zhukov personally, his actions were guided by his professional position as a communist dictator, who was trying to peg down the entire army, not solely one of his marshals.

A short-lived second chance

Aligning with Khrushchev

By the early 1950s, Zhukov’s public image was slightly rehabilitated, though he remained commander of the Ural. Then in 1953, he was recalled to Moscow. According to marshal’s memoirs, the call from Bulganin, who left him without an explanation. The very next day it was announced Stalin had died and major governmental restructuring was made. Zhukov became Bulganin’s deputy in the Ministry of Defense. Shortly afterward, two of them had a reconciliation or at least they expressed the need to leave their past behind them so they could work together. In the following weeks, Zhukov went through a speedy rehabilitation, regaining his political and party roles as well as favorable treatment in the press.

By June, he was to undergo the first test of loyalty. Khrushchev along with Malenkov, Molotov, and Bulganin asked him to personally lead the arrest of Beria. Zhukov was more than eager to comply. Beria was apprehended during a special politburo meeting, accused of treason, terrorism, and counter-revolutionary activity. He was shot soon afterward. In later years, the marshal showed great pleasure in his participation, saying it was his duty to partake in Beria’s demise. For Khrushchev, who without Beria secured his place as the new leader of the USSR, it was a sign of loyalty and he decided to keep Zhukov close to him.

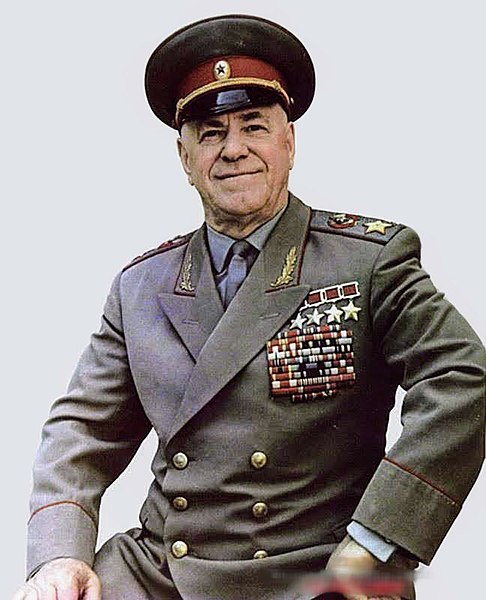

Marshal Zhukov in his later years

New heights

For a while, Zhukov was kept busy with the military matters, without too much meddling with party politics. However, in early 1955, Bulganin replaced Malenkov as the Premier of the USSR, whilst the marshal became the Minister of Defense. This rotation in the government put Zhukov in the political limelight, as he was also promoted to the highest positions in the CPSU. He started playing a more public role, becoming more visible in the Soviet media, along with various trips outside of the USSR. Most notably, the Red Army intervened in the Hungarian Crisis of 1956 under his command, where he exhibited determination and callousness.

However, throughout it all, Zhukov remained loyal to Khrushchev. Marshal voiced his support when it came to the denunciation of Stalin, but even more importantly, he defended Khrushchev when the Molotov-Malenkov group tried to depose him in June 1957. In the crucial moment when it seemed that the group had the upper hand, Zhukov acted aggressively and confidently, staving the ideological assault on Khrushchev, then using his position in the military to transport Khrushchev’s supporters to Moscow to partake in the hastily arranged Central Committee plenum. Finally, on the plenum itself, Zhukov attacked prominent members of the Molotov-Malenkov clique, connecting them with Stalin’s purges and abuse of power. These actions proved instrumental in bringing Khrushchev the final victory, whilst the deposers became the deposed ones. Such exhibition of loyalty should have made Zhukov Khrushchev’s right-hand man, but his fortunes weren’t going to last for much longer.

Quick downfall

While Khrushchev owed a lot to Zhukov for helping him stay afloat, his actions also made the First Secretary quite wary. Many of Zhukov’s moves were based on his position in the army, while his hero status gave him a lot of credence among the people. Thus, like before, Zhukov became too powerful in the eyes of the other politicians, especially Khrushchev. While the marshal was on a visit to Yugoslavia and Albania, a new plenum was organized, waiting for Zhukov to return. Upon his arrival, he was abruptly charged once again for Bonapartism, nurturing personality cult, political adventurism, straying from the party line, and curtailing the party grip over the army. Unlike with Stalin, this time not a single person stood up for Zhukov, not even his supposed friends. Thus by November 1957, Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov was forced into retirement, stripped of all his party and military positions. He spent the rest of his years writing and fishing, mostly staying away from the public spotlight, yet he remained a hero for most of the Soviet people even after he died in 1974.

Zhukov’s statue in Moscow, symbolizing the victory over Nazi Germany

What happened to Zhukov after WW2 highlighted the constant fear of Soviet politicians of strong and popular people, always feeling threatened in their governmental chairs. Many, including Khrushchev, publicly admitted that fear. Along with that, none of them liked that Zhukov, as a military officer, always tried to obey the letter of the law, disregarding personal positions in the party. Such actions certainly rubbed the wrong way many of the quite vain Soviet leaders. Nevertheless, they all needed people like Zhukov to deal with threats, be it the German invaders or Beria’s NKVD or Molotov’s supporters in KGB. Yet, once secured, Soviet politicians saw Zhukov as too much of a threat to be kept around. The irony is that Zhukov was aware that if he wanted, he could have staged a successful coup, backed by the army and the people. Yet he always insisted on loyalty to the state, the party, and the communist ideals.