Table of Contents

Introduction

When talking about the United States history, an unavoidable topic is the Civil War. It is often represented as a struggle for the liberation of African American slaves between the heroic Union in the north and the vile Confederation in the south. Similar descriptions and perceptions can be found throughout mainstream media, school textbooks, various arts, and more. By now it has become a dominant narrative which, despite its appealing image, is somewhat misrepresentative from reality.

Causes for the war

To understand why the Civil War wasn’t as clear-cut in regards to African American history, first it is important to understand why it started. Though many tend to begin this story with the election of Abraham Lincoln in November of 1860, or just years before that, its roots can be actually traced to the formation of the United States in the late 18th century. Since the Americans managed to fight off the oppressive British rule, smoldering sparks of division began to appear. Among the most important were the conflicting ideas of how extensive federal power should be as well as interpretations of liberty in face of abolitionism.

The topic of federal power over states can be simply linked with fear from further oppressions from a new ruling government, an idea that too strong central rule would lead to yet another monarchical tyranny where individuals would be left without much say or representation in the governmental decision making. In contrast, some of the Americans realized that a tighter federal rule could lead to a better-developed country, more unified and cohesive. Here it should be pointed out that virtually no politician in the US ever advocated for an overreaching federal government.

The issue of slavery was more complex than that. Due to different economic development, the northern US states had a relatively small number of slaves as their economies were more linked with industry. In contrast, the southern states relied on forced labor for work cash crops, a system established by early American colonists in the 17th century. Thus, for some Northerners the issue of slavery was mostly a moral one, as they quite rightfully deemed it as an inhumane despicable act. Yet, for most Southerners it was the foundation of their society, and they were prepared to defend it. Also worth pointing out is the fact that most Northerners weren’t really concerned about the issue.

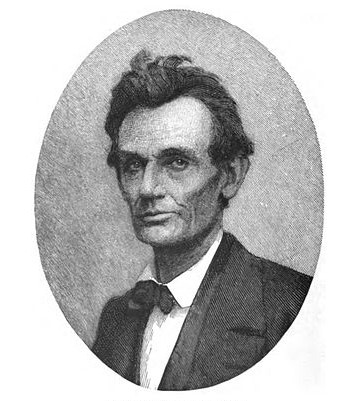

An 1860 engraving of Abraham Lincoln Wiki Commons

As US politics evolved through the first half of the 19th century, abolitionism began to prevail, championed by the Republican Party from the 1850s. With that, the fragile compromise between the North and the South began to crumble. Much more influential and increasingly richer Northerners began spreading the idea of banning slavery altogether, at least in part motivated by the capitalist ideals of free labor. However, their ultimate goal wasn’t to force the southern states to ban slavery, but instead to contain it from spreading into newly formed US territories in the west. This can be attested by Lincoln’s inaugural speech in march of 1861:

“… I declare that I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists…”.

Regardless, the election of Abraham Lincoln, coupled with the Republican majority in all the levels of the federal government, was enough to push southern states into secession. They feared that republicans, unconstrained by the opposition, would use their position in central power to force them into abolition.

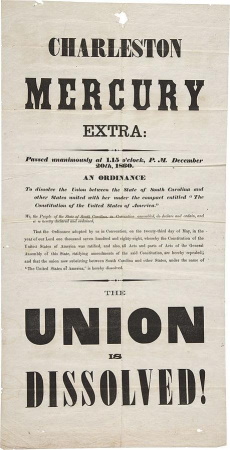

Proclamation of South Carolina’s secession Wiki Commons

In late 1860 and early 1861, seven southern states withdrew from the United States (Union) and formed the Confederacy. By early April of 1861, the chaos finally erupted into war after the southern troops attacked a Union garrison in South Carolina. The attack not only started the war but also strengthened the resolve of the Northerners to fight. However, their goal in the war wasn’t to end slavery but to preserve the Union. Lincoln himself declared that no state could legally depart from the Union, while his oath was to enforce the law and protect federal property throughout the United States.

The issue of slavery as a war aim

Although abolition wasn’t the goal of the Union at the start of the Civil War, all major politicians realized that issue of slavery was the underlying root of the conflict. With that, the Northerners realized that if their goal of preserving the unity of the United States, they had to deal with that problem as well. Over the first year of the war, abolition as a goal of war began to crystalize, before it culminated in the Emancipation Proclamation. It was decreed in September of 1862, legally freeing all slaves from the separatist states. Of course, the majority of the estimated 4 million enslaved African Americans were out of the Union’s reach in the Confederacy, meaning their status remained unchanged for some time. Furthermore, the proclamation didn’t dictate abolition in Union states. Yet, it redefined the war. For the Northerners, it reframed the conflict as a struggle against slavery, while it reaffirmed the southern resolve to defend it. Thus, abolition and in turn emancipation, at least on the surface, became the main war aim.

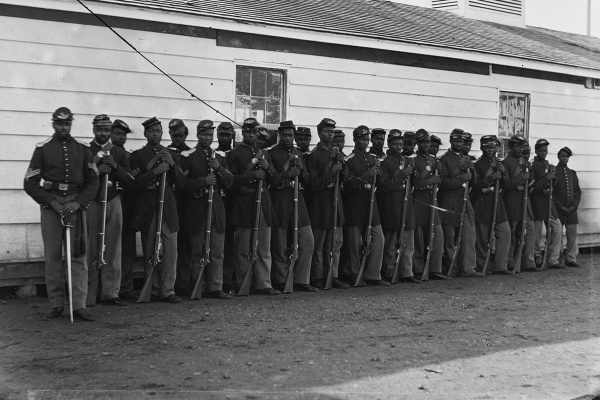

However, it should be kept in mind that such tactics also contributed directly to the war effort. It would undermine the southern economy and security by prompting slave rebellion. Furthermore, it enabled the formation of the African American Union troops, promulgating volunteering both from escaped slaves and freemen. With this, the Union forces grew their numerical superiority as about 200,000 African Americans enlisted to serve. Nonetheless, their struggles during the war proved that despite the government’s propaganda, the ultimate goal of the war wasn’t racial equality. During the war, the Union African American soldiers were constantly mistreated, beaten, forced to work harder, while also being given less pay and almost no way to rise in ranks, leaving them in command of white Northerners. For most, it was clear that the Civil War wasn’t there to combat racism. Yet, they persisted in their struggle, as many still saw southern slavery as worse. In that vein, the Confederate troops didn’t extend the common treatment for prisoners of war to the captured African American soldiers, but often killed them or sent them back to slavery.

Union’s so-called Colored Infantry from the Civil War The Atlantic

Despite the discrepancy between official policy and the reality on the field, the Republican government pushed for nationwide abolition through the 13th Amendment which was passed in January of 1865. It was a decisive stroke, while the Republicans were still unopposed, to prevent the issue of slavery from rising up again. By early 1865 it was clear that Union was achieving supremacy on the battlefield. Thus, in May of 1865, the Confederacy was defeated, and with it came the end of slavery in the US. The rebellious states were forced to recognize the 13th Amendment which was ratified in December.

A fruitless victory

After the war was won, the southern states remained under the military rule of the Union in the so-called Reconstruction Era. For a while, they remained politically outside of the US system. Despite losing their stalwart of abolitionism, as Lincoln was assassinated in April of 1865, the Republicans pushed for two more amendments. The 14th Amendment (ratified in 1868) defined citizenship and gave it to all the freed slaves, while the 15th Amendment (ratified in 1870) guaranteed the voting right regardless of color or previous servitude. Such legal actions were furthered by the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (enacted in 1866 but ratified in 1870) which guaranteed equality in front of the law regardless of race. Those actions are today heralded as victories over racism and inequality, but once again their ultimate goal was slightly different. On one hand, these laws cemented the fate of slavery, working to prevent any further wars over the issue, while also playing to the hand of the Republicans who passed them. The majority, if not all, African Americans who gained the voting rights would assumably become Republican supporters, adding millions of voters for them.

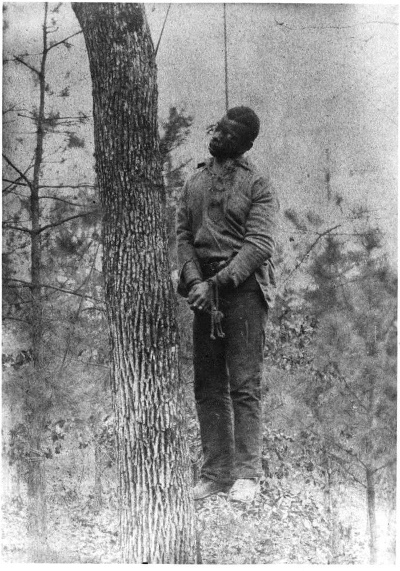

A photo of a lynched African American commons-wikimedia

Regardless, had the faultiness stopped at the motives behind the lawmaking, it would remain a clear victory for the African Americans. However, it wasn’t long after the end of the war that racism once again showed that ideas weren’t easily beaten through battles. Throughout the south, many local mobs began attacking newly freed African Americans, whilst lynching became more common than before. Symbolizing radical racism under the shroud of legality was KKK, a so-called social club formed in late 1865, which continued to terrorize colored Americans without much restraint. Further undermining the gains from the Civil War were the so-called Jim Crow laws that began to appear during the 1870s. Those were state regulations that basically institutionalized racism in the south through the formulation “equal but separated”. With those, African Americans began facing segregation as well as political disenfranchisement through poll taxes, literacy, and residency requirements. Overall, the idea of basic equality and civil rights for the African Americans remained a far dream.

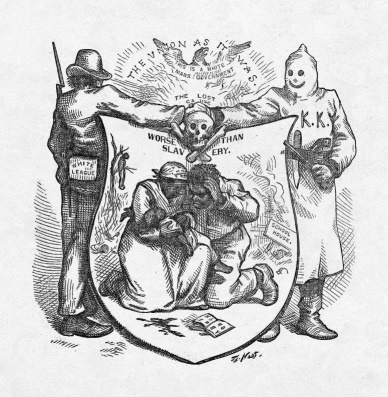

Newspaper cartoon depicting fate of the African Americans worse than slavery commons-wikimedia

However, it would be wrong to limit racism just to the Southerners. Despite opposing slavery as a concept, many Northerners didn’t think much of the African American population. Such notions could be attested through a sizable opposition towards the mentioned amendments, especially in the western states that remained mostly untouched by the war. Furthermore, a sizable portion of the common population feared that their cities would be overrun by freed slaves looking to take their jobs and other similar notions of African Americans disrupting their societies. Thus, even in the supposedly abolitionist North, colored people would still face racism and prejudice. Even worse, when Northern politicians realized that the African American plight moved away from the public eye, they stopped caring as well. Because of that, throughout the 19th century, the federal government continued to mostly look away from the civil rights issues while fully being aware of the rampant mistreatment of African Americans across the United States.

Conclusion

In the end, it is hard to deny that the victory achieved through the Civil War was important. No matter what, it ended slavery and legally gave basic civil and political rights to millions of African Americans. However, those civilizational achievements failed to fully actualize in form of equality and emancipation. As such, it could be seen as a hollow victory, where reality still trailed the formality. One of the reasons for such an outcome is the fact that the Civil War wasn’t actually fought for the liberation of African Americans, but that their freedom came as a byproduct of maintaining the unity of the US. In the words of President Lincoln himself:

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.”

It is a perspective that is important to keep in mind, as it sheds a lot of light on contemporary issues plaguing American society and the somewhat erroneous public perception of the Civil War.

Sources

- Alton Hornsby [edited by], A companion to African American history, Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

- Colin A. Palmer [editor in chief], Encyclopedia of African American culture and history:the Black experience in the Americas, Thomson Gale, 2006.

- Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States: 1492-Present, HarperCollins, 2003.

- James Ciment, Atlas of African American history, Facts On File, 2007.

- Mary Beth Norton et al., A People & a Nation: A History of the United States, Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2008.

- Robert V. Remini, A Short History of the United States, New York, HarperCollins Publishers, 2008.

- Susan-Mary Grant, A Concise History of the United States of America, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- U.S. Department of State, Outline of U.S. History, Washington DC, Bureau of International Information Programs, 2005.

References

- American Civil War

- Black History Milestones

- African Americans from archives.gov

- American Civil War Era